Hong Kongers are Britain’s fastest growing community.

But those supporting new arrivals have told Sky News of their concerns about the impact of large numbers arriving in a short space of time – even warning of social conflict unless resources are properly managed.

And in spite of the millions who are eligible to come to the UK, some believe it should be extended.

The UK opened its borders to three million Hong Kongers and their dependents – potentially five million people – following China’s democracy crackdown.

And they’ve been arriving in the UK or applying to come here – on average – at a rate of 2,500 a week since January.

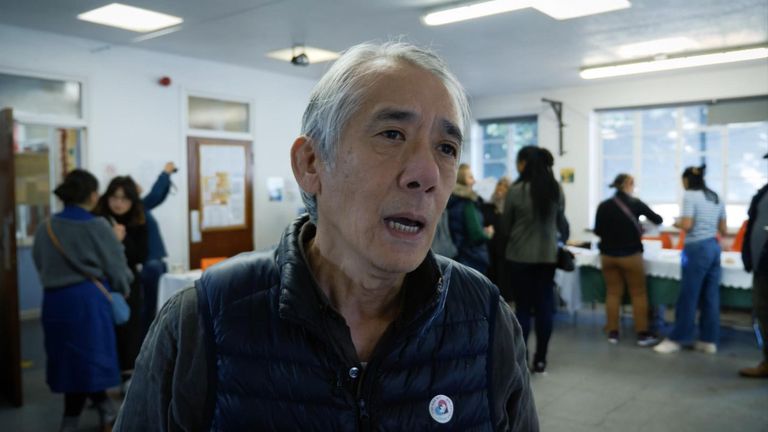

Richard Choi came to the UK from Hong Kong 13 years ago. He now lives in Sutton in Surrey – the kind of suburb which is proving popular with newly arrived Hong Kongers.

Mr Choi is now helping people settle in and says you can see with your own eyes how the demographic has changed just by walking down the high street.

He says: “A lot of local people feel the same. After the pandemic they got back to the high street and they kind of feel ‘hey it’s different’ because there are a lot of new faces, especially Chinese and Hong Konger faces.”

But he is worried that new arrivals will stretch local resources and facilities and that risks alienating the local population.

He says: “If we do not contribute the resources evenly it means that the local people may be angry about maybe some of the resources being taken and that will have social conflict.

“For new arrivals coming here it will be very easy to have social conflict or racism.

“Maybe people will see them as the enemy or competitors. They may feel like the immigrants took their jobs and feel angry towards them.”

In Sutton, walking down the high street with Mr Choi, it doesn’t take long before we bump into the Wong family – who arrived two weeks ago.

Mr Choi hears Cantonese voices and goes over to introduce himself to mum and dad Brian and Joanne and their five-year-old daughter Melissa. It’s their first time in the UK but they’re not alone.

Mr Wong says: “Some of our friends and relatives have also come to the UK – especially Sutton and especially those with kids.”

Melissa has a school place but the Wongs say others they know have struggled to get their children into school.

Places like Sutton are popular because they are still commutable to London but far enough out for people to think they will get better schools and bigger homes.

Finding accommodation is another key issue – with some of those we spoke to saying a lack of UK credit history means some landlords have asked for a year’s rent in advance.

One woman we met – who didn’t want to give her real name – said she felt without the help of the church she would have struggled to find somewhere to live.

She told us: “The demand is very high and the available flats or houses is pretty limited so I started to recognise Sutton is not easy to find an available place to live in. But luckily, praise God I found some Hong Kong people are helping.”

The woman – who we are calling Anthea – pads up the stairs in her new home, past a bedroom door which is open. You can see her suitcases inside. In the lounge there are boxes being unpacked.

Anthea came with her son but her husband has remained in Hong Kong to look after elderly parents.

Everybody reports a warm welcome but Anthea echoes the concerns we are hearing: “One worry is if there are many Hong Kong people coming to the same place then maybe the local people will worry that we have got their placement of work or placement of school or other kinds of resources.”

We met a number of new arrivals in Sutton – and Anthea is not alone in wanting to hide her identity.

Many of those we spoke to said in spite of arriving safely in the UK they are careful about what they say because of security concerns for relatives still in Hong Kong.

Raymond – not his real name – also lives in Sutton and has come to the UK with his wife and young child.

A collection of children’s toys by the side of the sofa is an indication of the life they left behind.

It includes a small model of a traditional Hong Kong minibus.

He told me: “I’ve no regrets at all. We were living in such a tense atmosphere over the last few years the day I arrived I feel relieved.

“Finally we can plan our future in the longer term. Finally I don’t have to worry about my kid’s education – I don’t mean they have to go to Oxford or Cambridge kind of thing. It means I don’t need to worry whether he’ll be brain-washed. He can be educated here in a more healthy environment.”

It’s not just homes and school places the new arrivals need to find – but also jobs.

Another stumbling block some Hong Kongers are finding is their qualifications aren’t recognised in the UK, so an estimated 40% are thinking about setting up their own businesses.

Eric Wong came nine months ago and had never been to the UK before. He left behind a successful business selling tea leaves but brought with him his entrepreneurial spirit.

Happy to reveal his identity and his dreams he’s decided there’s a market in the UK to make and sell Hong Kong milk tea – a traditional drink which is a unique blend of leaves served very milky and sweet.

He’s now got a licence to produce his secret blend in his kitchen.

Mr Wong isn’t confident enough to speak to us in English – he’s still learning, but understands that to truly integrate that has to change.

He says: “I’m going with the flow. I will learn English and hope to blend into the community.

“It will be mutually beneficial. Hong Kong people will bring investment and new ideas. And on the other hand we are very thankful the local community has accepted us and given us a safe place to live in.”

But not everyone is optimistic about the future.

Enoch – not his real name – shares videos with us – microphone to his mouth – of him leading a demonstration outside the British consulate in 2019.

Enoch says when the opportunity to travel to the UK came up last year he pretty much got on a plane within a few days.

But he arrived at a time of lockdowns and restrictions and before the official BNO visa scheme was launched in January this year.

He says he couldn’t get a job and by the time the visa scheme opened he’d used up his £10,000 in savings trying to survive.

With his money having run out Enoch says he’s now homeless – staying on people’s floors and sofas – and reliant on food banks and hand-outs.

He says: “I packed everything in two or three days and came over. Full of hope I could rebuild everything here. The reality is devastating.”

Enoch says landlords want proof of income and he couldn’t get a National Insurance number to find work.

He says: “To be frank I had a jolly good life but I made a decision to come over here because I felt I would potentially get persecuted.”

Now Enoch says he feels betrayed by the British government because he says he can’t afford to apply for the visa or the healthcare costs associated with it.

Condemning it as a scheme for the well off he says: “I can’t see the future. Every single day I’m struggling. Where am I going to sleep and where will I be tomorrow? I’ve lost hope.”

The Home Office told us those on the BNO route can apply for a change of conditions to have their No Recourse to Public Funds condition lifted in the event they become destitute.

A spokesperson said: “The BN(O) route is an unprecedented and generous offer reflecting the UK’s historic and moral commitment to the people of Hong Kong who chose to retain their ties to the UK by taking up BN(O) status at the point of Hong Kong’s handover to China in 1997.

“The route offers long-term safety and stability for BN(O) status holders and their families enabling them to come to the UK to live, study and work in virtually any capacity on a pathway to citizenship.

“The cost of the visa has been set lower than many other visa routes to the UK.”

The UK has offered a new life to those who were born before Britain handed back control of Hong Kong in 1997 and the government has said it estimates around 350,000 Hong Kongers will come in the next five years.

Others believe the figures will be higher and the parameters of the scheme need to be looked at.

Some believe the scheme fails to take into consideration many younger activists who were born before 1997.

Krish Kandiah is a member of the government’s Hong Kong task force.

He tells Sky News: “All the Hong Kongers that I’ve met in the UK are really grateful for the UK government’s hospitality through the BNO route.

“But I am personally concerned there are some people who need to come out of Hong Kong who don’t qualify for the BNO route and I want to make sure we are equally hospitable to those people – that that’s based on need rather than geniality or financial status.”

He also believes the numbers who will eventually come – even amongst those currently allowed – will be higher than forecast, saying it will eventually turn out to be the biggest planned migration to the UK from outside Europe since Windrush.

He says: “The Home Office estimates 150,000 Hong Kongers will come this year alone. Speaking to a friend in Hong Kong, schools are closing down because so many children have moved.

“I think this is just wave one – these are the early adopters these are people with money and a bit more social agility and capacity to move quickly, whilst others will have to wrap up businesses, sell houses and make plans for elderly relatives and that takes some time.

“So wave two I think is coming soon and a lot will depend on how wave one get on.

“The door is open now. The BNO route is in action and I don’t think there’s a statute of limitations on it.”

He also shares concerns about the social impact of so many people arriving over a relatively short period of time if the scheme is not properly managed.

He says: “‘I think there’s great potential for this migration to go really well because many people recognise the incredible skills and abilities that people from Hong Kong have and how much richer and more vibrant our culture can be because they’re here.

“I think there will also be a minority of people that will have maybe more of a negative perspective on this migration and that’s why it’s important that civil society steps up and offers a really warm welcome.

“I think it’s vital we get this right. At the very beginning of the BNO route opening up it coincided with a spike in race-based hate crime against people of southeast Asian appearance but it worked out in some really horrible incidences against people of Chinese appearance in the UK.

“We know when we get it wrong it leads to all sorts of terrible consequences but when we get it right everybody wins.”

The government says it’s pledged £43m for this financial year to support BN(O) status holders in accessing housing, work and educational support to enable people to integrate successfully into their new communities.

But it’s not entirely about easing the concerns of local people over the distribution of resources.

There’s an added layer of complexity – which involves Hong Kong-Chinese relations.

In north London we met Jabez Lam from Hackney Chinese Community Services who was holding an afternoon tea party for all new arrivals in the area – including Hong Kongers.

He revealed concerns that some traditional Chinese groups and businesses in the UK – who are loyal to the communist government in Beijing – may not be as welcoming.

He claimed: “Through these organisations the Chinese government are exerting their influence to try to make a hostile environment to put off Hong Kongers.

“There have been online messages through WhatsApp and Facebook and social media calling for people not to employ Hong Kongers and not to do business with Hong Kongers.

“These are the kinds of direct interference that the Chinese government are able to influence in this country.”

It’s a huge melting pot of issues born out of Britain’s promise to stand by the citizens of its colonial past who look to Britain not China for their future.

Source: Read Full Article