The Supreme Court on Friday struck down the Biden administration’s massive student loan forgiveness program, ruling that the Education Department had exceeded the authority granted to it by Congress to alter loan conditions in a national emergency like the coronavirus pandemic.

The ruling was six to three, with the court’s Republican-appointed conservative majority delivering a major setback to President Biden’s policy agenda over the vigorous dissent of its three Democratic-appointed liberal justices. Here are some key excerpts.

A central part of the dispute was how expansively to interpret a provision of the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003, or HEROES Act, in which Congress said that the secretary of education “may waive or modify” any provision of federal student loan programs in a declared national emergency. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that the Biden administration had stretched the words too far.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

The authority to “modify” statutes and regulations allows the Secretary to make modest adjustments and additions to existing provisions, not transform them. … We hold today that the Act allows the Secretary to “waive or modify” existing statutory or regulatory provisions applicable to financial assistance programs under the Education Act, not to rewrite that statute from the ground up.

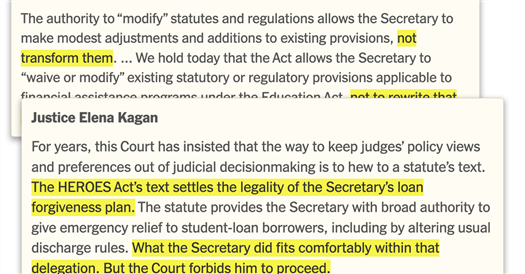

In the dissenting opinion, Justice Elena Kagan rejected Chief Justice Roberts’s interpretation of the text of the law. She accused the majority of abandoning the usual conservative ideology of textualism, or interpreting statutes in ways that hew to the words themselves.

Justice Elena Kagan

For years, this Court has insisted that the way to keep judges’ policy views and preferences out of judicial decisionmaking is to hew to a statute’s text. The HEROES Act’s text settles the legality of the Secretary’s loan forgiveness plan. The statute provides the Secretary with broad authority to give emergency relief to student-loan borrowers, including by altering usual discharge rules. What the Secretary did fits comfortably within that delegation. But the Court forbids him to proceed.

Chief Justice Roberts supplemented the majority’s interpretation of the words “waive or modify” by invoking the so-called major questions doctrine, a creation of conservative justices that says courts should strike down regulations and other agency actions that raise “major questions” if Congress was not explicit enough in authorizing them. (The court expanded and entrenched that doctrine in a case last year striking down an Environmental Protection Agency plan to curb carbon emissions from power plants.)

In a concurring opinion, Justice Amy Coney Barrett fleshed out the doctrine and argued that it applied to the student loan case.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett

It is obviously true that the Secretary’s loan cancellation program has “vast ‘economic and political significance.’” Utility Air, 573 U. S., at 324. That matters not because agencies are incapable of making highly consequential decisions, but rather because an initiative of this scope, cost, and political salience is not the type that Congress lightly delegates to an agency. And for the reasons given by the Court, the HEROES Act provides no indication that Congress empowered the Secretary to do anything of the sort.

Justice Kagan’s dissent was scathing about that move as well.

Justice Elena Kagan

The opinion ends by applying the Court’s made-up major-questions doctrine to jettison the Secretary’s loan forgiveness plan. Small wonder the majority invokes the doctrine. The majority’s “normal” statutory interpretation cannot sustain its decision. The statute, read as written, gives the Secretary broad authority to relieve a national emergency’s effect on borrowers’ ability to repay their student loans. The Secretary did no more than use that lawfully delegated authority. So the majority applies a rule specially crafted to kill significant regulatory action, by requiring Congress to delegate not just clearly but also microspecifically.

The case also involved a technical dispute: whether the plaintiffs had legal standing to challenge the Biden administration’s program. (The court dismissed a parallel case on Friday brought by two student loan borrowers, ruling that the injury they claimed to have suffered was not sufficiently linked to the forgiveness program to give them standing.)

Several Republican-controlled states filed the lawsuit, and the most important turned out to be Missouri, which has created a nonprofit government corporation called MOHELA that participates in the student loan market and collects fees.

While MOHELA itself did not file the lawsuit, and its fees do not go into state coffers, Chief Justice Roberts wrote that the impact of the student loan forgiveness program on the agency created a sufficient injury to Missouri to give the state itself standing to sue.

Chief Justice Roberts

By law and function, MOHELA is an instrumentality of Missouri: It was created by the State to further a public purpose, is governed by state officials and state appointees, reports to the State, and may be dissolved by the State. The Secretary’s plan will cut MOHELA’s revenues, impairing its efforts to aid Missouri college students. This acknowledged harm to MOHELA in the performance of its public function is necessarily a direct injury to Missouri itself.

Justice Kagan accused the majority of engaging in legal contortions because they wanted to give themselves an opportunity to strike down a program they did not like.

Justice Elena Kagan

The majority’s opinion begins by distorting standing doctrine to create a case fit for judicial resolution. But there is no such case here, by any ordinary measure. The Secretary’s plan has not injured the plaintiff-States, however much they oppose it. And in that respect, Missouri is no different from any of the others. Missouri does not suffer any harm from a revenue loss to MOHELA, because the two entities are legally and financially independent. And MOHELA has chosen not to sue—which of course it could have. So no proper party is before the Court. A court acting like a court would have said as much and stopped.

Chief Justice Roberts put an addendum on his majority opinion telling the public not to interpret Justice Kagan’s dissent as a sign of discord at the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Roberts

It has become a disturbing feature of some recent opinions to criticize the decisions with which they disagree as going beyond the proper role of the judiciary. … We have employed the traditional tools of judicial decisionmaking in doing so. Reasonable minds may disagree with our analysis—in fact, at least three do. … We do not mistake this plainly heartfelt disagreement for disparagement. It is important that the public not be misled either. Any such misperception would be harmful to this institution and our country.

Charlie Savage is a Washington-based national security and legal policy correspondent. A recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, he previously worked at The Boston Globe and The Miami Herald. His most recent book is “Power Wars: The Relentless Rise of Presidential Authority and Secrecy.” @charlie_savage • Facebook

Source: Read Full Article