For many Americans, cars became a lifeline and refuge during the pandemic, even as newly sparkling air over locked-down cities highlighted their darker side. Soul-searching over commuting and climate change was balanced by hope that cars might clean up their act via electricity, and allow new generations to fall for their beauty and ingenuity.

That wrench-tight tension is at the heart of Automania, an exhibition opening at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan on Sunday — July Fourth, a holiday that has come to symbolize motorized freedom and parade-queen convertibles. In that spirit, the public might be urged to visit MoMA via mass transit; but in this case, pack the kids in the S.U.V. and have at it.

As this shrewdly curated show reveals, that yin-yang of cars dates to the industry’s earliest years, and to those of MoMA itself.

Automania takes its name and inspiration from a 1963 Oscar-nominated animated short, “Automania 2000.” That piece is the work of John Halas and Joy Batchelor, the British husband-and-wife team best known for a 1954 version of George Orwell’s “Animal Farm.” Their short imagines a future of science-bestowed wonders, like limitless “electrohydromagnetic” energy, appetizing factory food made from petroleum, and a craze for ever larger and faster rides that hatches the “40-foot supercar.” (The S.U.V. was apparently beyond the most fertile imagination.)

Problems ensue: New York and other cities are piled skyscraper-deep with pancake stacks of cars. Their “car dwellers” appear happy enough, putting up “Home Sweet Home” signs, but they’ve been stuck inside for years, in a striking pandemic parallel.

Here in 2021, crosstown traffic at least crawls, and the world continues to grapple with the fallout from personal transportation.

“It does seem like we’ve come to another critical juncture in our relationship to the automobile,” said Juliet Kinchin, who curated the MoMA exhibit with contributions from Paul Galloway and Andrew Gardner.

Yet the exhibit, drawn almost exclusively from the museum’s own collection, is never dogmatic, walking a painted white line between critique and celebration.

“We’re hoping it will deepen and spark further debate, but also joyous appreciation of the automobile’s innovation, tech and social transformation,” Ms. Kinchin said.

Paintings, sculpture, photographs, posters, films, models, road signs and car components show how the automobile has transformed every aspect of our culture, landscapes and cities — and fueled the imaginations of artists.

The authoritative array bookends three centuries, including Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1898 lithograph “The Automobile Driver.” It depicts the artist’s doctor cousin, bedecked in fur driving coat, gloves and goggles, speeding past a Parisian woman and her yapping dog, oblivious to fumes and dust in his wake.

Artists — as varied as the Dadaists and Italian Futurists or car-obsessed designers like Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright — instantly grasped the power and possibilities of the automobile. The Futurist Giacomo Balla produced more than 100 studies of cars, including the coruscating, kaleidoscopic beauty of 1912’s “Speeding Automobile.” By 1915, the exhibit catalog says, the avant-garde painter Francis Picabia had asserted that “the genius of the modern world is machinery, and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression.” Le Corbusier compared a sleek Delage Grand Sport to the Greek Parthenon, seeing both as “reflections of the needs and spirit of their respective age.”

Advertising got aboard early, including by leading graphic artists, such as Lucian Bernhard’s 1914 poster of a cosmically igniting Bosch spark plug. Then as now, artists and companies insinuated shameless links between driving and personal power and sex. A 1907 ad by the Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela for a Swedish car company shows its eccentric chief executive, known as the “flying baron,” driving through a starlit sky, abducting a stylized nude maiden named Kyllikki. In this updated Finnish epic, the daredevil hero’s wood sled is replaced by a phallic car, in the Nordic National Romantic style influenced by Art Nouveau.

Latest Updates

The exhibit’s billboard-size names include Edward Ruscha, Andy Warhol, Robert Frank, Charles Sheeler and Margaret Bourke-White. Edward Hopper’s 1940 painting “Gas” moves its artist’s hollowed-out view of American isolation from his familiar city diner to a fuel station in the middle of the American nowhere. A lone attendant, in vest and tie, stands sentry at the pumps, awaiting a car that may never come.

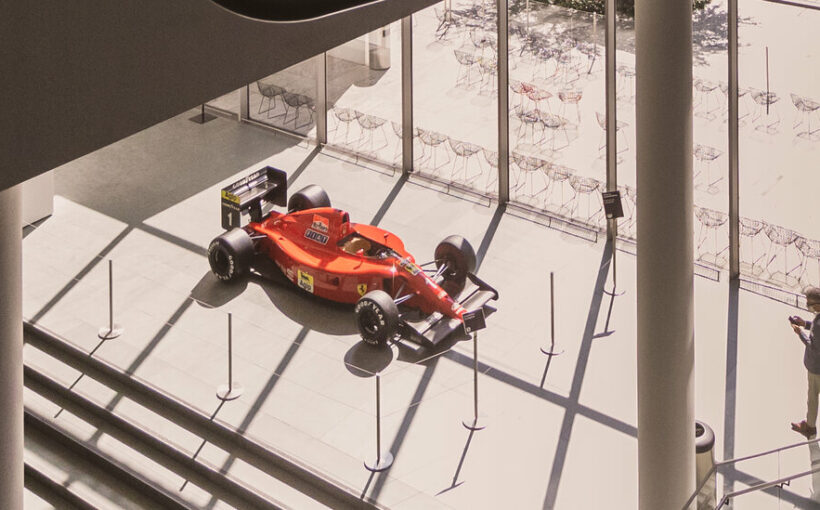

Automania also highlights 10 examples of pathbreaking auto design, including a stogie-stretched, 1963 Jaguar E-Type Roadster; a 1990 Ferrari Formula 1 racer; and an adorable 1963 Airstream Bambi trailer. The aluminum-skinned Bambi — named by the company founder Wally Byam, during his 14,000-mile caravan through Africa in 1960, for a tiny deer known as “O’Mbambi” in a Bantu dialect — became a fixture of American highways, reliably towed by a family station wagon.

MoMA’s most recent tire-kicking acquisition is a Citroën DS sedan. It’s a late, 1973 example of the classic created by Flaminio Bertoni of Italy and the aviation engineer André Lefèbvre. The DS remains among the most lauded, fetishized designs of the 20th century, despite its iconoclastic proportions. The name is a French play on “Deesse,” the pronunciation of its word for “Goddess.”

In 1955, the year of the DS’s earthshaking introduction, the French critic and philosopher Roland Barthes drew another artistic line in the sand. He declared the DS “almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object.”

For Barthes, Le Corbusier and others who likened cars to religious temples and other idealized forms — sometimes with what a mechanic might describe as a tendency toward overheating — it’s telling that they’re so often men. Still, the DS was magical in other ways: an Apple ahead of its time, with pivoting headlamps, a self-leveling suspension and novel electronics.

And the exhibit spotlights often-overlooked contributions of women. A 1958 General Motors film promotes its “Damsels of Design,” the women from Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute recruited by Harley Earl, the towering G.M. figure who essentially birthed modern automotive styling, along with the tail fin and the Corvette. Even then, the patronizing “Damsels” name rankled the women, whose innovations included childproof doors, retractable seatbelts and lighted vanity mirrors.

Even Picasso had a surprising go at the automobile, in the 1951 bronze “Baboon and Young.” Ms. Kinchin explained that Picasso had nicked two toy cars from his son, sandwiching them to create the baboon’s mouth from dual radiators, its eyes framed by a windshield, a leaf spring forming its spine and tail. The man-machine (and animal) hybrid — an enduring fascination, from Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” to Kraftwerk’s musical robots — is essentially passed down to the baby baboon clinging to its mother’s breast. (Kraftwerk’s album cover for 1974’s “Autobahn” is also here in lithograph form.)

“To me, there’s so much there about how cars have gotten into our heads,” Ms. Kinchin said. “Physically and psychologically, they become an extension of ourselves on many levels.”

As curators explored MoMA’s vast holdings, they realized that even this generous exhibit could make room for only a small fraction of auto-related works.

“We were amazed and frustrated at how little we could actually show,” Ms. Kinchin said. “The subject is so rich.”

MoMA has always delighted in provocative questions about what qualifies as modern art. Before becoming MoMA’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr. took his modern-art students at Wellesley to see New York’s 1928 National Automobile Show. The architecture curator Philip Johnson’s “Machine Art” show in 1934 featured engine pistons, ball bearings and a dashboard clock among its works.

In 1951, MoMA trumpeted its show known as 8 Automobiles with a news release: “Museum to Open First Exhibition Anywhere of Automobiles Selected for Design.” The exhibit was so popular that it was reprised two years later as Ten Automobiles. One addition was a Studebaker Commander Starliner Coupe, the knee-wobbling pillarless coupe once credited to the industrial-design giant Raymond Loewy, but largely the work of his employee Robert Bourke.

A curator, Arthur Drexler, with polemical intent — today we’d call it “trolling” — described the initial 8 Automobiles as “hollow, rolling sculpture.”

The catalog notes that “the designation bewildered the public and journalists alike,” including a 1951 New York Times critic who imagined a MoMA tour for a just-arrived Man from Mars, wondering what on earth cars were doing in a museum.

“Wonder how the public will take to this exhibition. People are touchy about cars,” the prophetic alien decides.

People, not least New Yorkers, remain touchy. But only the most contentious sort would argue that automobiles weren’t worthy of artistic or design consideration.

“You don’t have to be a driver or own a car to have powerful memories or associations about cars in your life,” Ms. Kinchin said. “Everyone has a car story. Everyone on some level can identify with the car.”

Source: Read Full Article