There are various estimates of India’s debt to GDP ratio, but the consensus is that that it would be over 80 per cent at the end of the current fiscal year.

India may not face cuts in sovereign ratings just because its debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio is likely to move closer to 90 per cent in the current fiscal year and the liabilities may remain high even during next fiscal year because of the demand for fiscal expansion.

However, there has to be a credible debt management road map once the economy returns to its normal level, experts have cautioned.

The upcoming Budget may give some signals on that path, they projected.

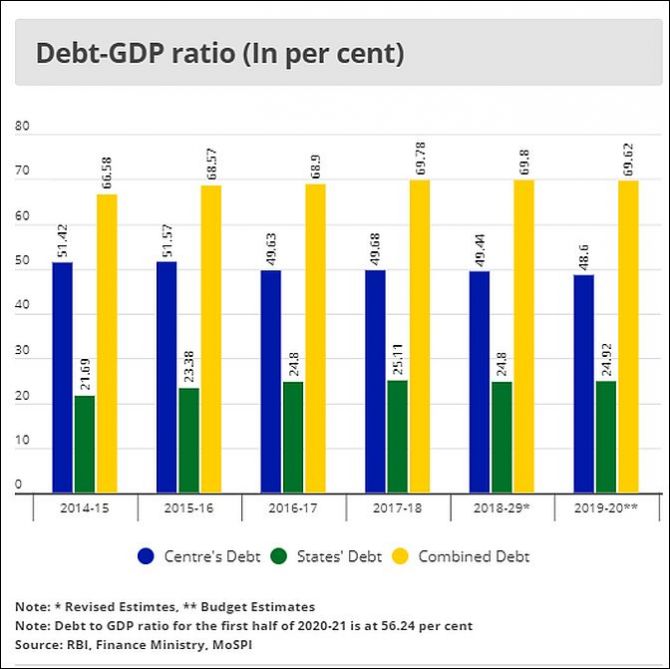

The Union government’s debt touched 56.2 per cent of GDP as of September 30 this fiscal year against 46.5 per cent at the end of 2019-20 (actuals, which are different from what is presented in the chart).

For the purpose of calculating debt as a proportion of GDP, the size of the economy in the second half of 2019-20 is taken into consideration and hence debt could be quite high at the end of the current fiscal year because of a further rise in liabilities and the shrinking of the economy.

The economy is officially projected to shrink 4.2 per cent at current prices in the current fiscal year.

The states’ outstanding liabilities were 25.8 per cent as of March 2020 (actuals, which are different from chart).

If one conservatively assumes that the trend is maintained as of September-end this fiscal year, the outstanding liabilities of the Centre and the states may have crossed 80 per cent.

It should be noted that India’s debt is not a straight addition of that of the Centre and the states because there are certain overlapping items.

There are various estimates of India’s debt to GDP ratio, but the consensus is that that it would be over 80 per cent at the end of the current fiscal year.

It could even reach closer to 90 per cent.

For instance, Thomas Rookmaaker, director, sovereign ratings, Fitch Ratings, estimated it at 89 per cent of GDP, while SBI group chief economic advisor Soumya Kanti Ghosh projected it to be 87.6 per cent.

One of the potential triggers for a downgrade of sovereign ratings would be a failure to reduce the fiscal deficit after the pandemic recedes, and to put the general government debt to GDP ratio on a downward trajectory over the medium term, Rookmaaker said.

“The Budget might include signals about the authorities’ medium-term fiscal plans. In addition to fiscal consolidation, the level of medium-term growth will be an important ingredient of the debt trajectory,” he said.

M Govinda Rao, chief economic advisor at Brickwork Ratings, said an important factor was the steps the government intended to take to achieve debt sustainability once normalcy was restored.

“It is important for the government to amend the FRBM (Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management) Act, laying out a credible road map from 2022-23 for fiscal consolidation in the forthcoming Budget towards achieving sustainable debt.”

The 15th Finance Commission recommendation on this count could provide guidance in working out the road map, he said.

The Medium Term Fiscal Policy-cum-Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement, tabled along with the Budget papers in February 2020, estimated the Centre’s debt at 50.1 per cent of GDP in 2020-21.

All the three global rating agencies — Standard & Poor’s, Fitch Ratings, and Moody’s — have assigned India the lowest investment grade.

Rao said, “The outstanding debt of 90 per cent of GDP may not impact credit ratings.”

To buttress his point of view, Rao said a significant increase in the outstanding liabilities of the governments was owing to disruption in economic activities caused by Covid.

“It is a global phenomenon and India is not an exception,” he said.

Rao, who is former director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy and former member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, said this situation of rising debt was not due to policy or governance-related issues.

The government had to support economic activities through public spending in the wake of the sharp contraction in revenues.

“Rating agencies will take this into account.”

Vishrut Rana, Asia-Pacific economist for S&P Global Ratings, said India’s support from fiscal policy was still significantly lower than that of emerging market peers.

He cited IMF data that showed that India’s fiscal stimulus measures were about 1.8 per cent of GDP compared with 3.8 per cent for global emerging markets.

Rana said the high-frequency data showed that consumer spending was recovering gradually, while external demand was robust.

“We expect recovery to 10 per cent GDP growth for FY22,” he said.

Moody’s Investors Service refused to comment on the issue.

- Budget 2021

Source: Read Full Article