SINGAPORE/SEOUL (Reuters) – China’s economic setbacks have darkened the outlook for countries in its orbit, from South Korea to Thailand, as a sharp factory slowdown and trade bottlenecks in the world’s second-largest economy hit Asia on the supply as well as demand sides.

China’s gross domestic product faltered in the third quarter, data showed this week, with growth hitting its weakest in a year, hurt by power shortages, supply chain snags and a property market crisis.

For China’s trading partners, the slippage presents new risks to what is shaping up to be a bumpy global recovery from the pandemic slump.

“Yes, growth elsewhere, namely the U.S. and Europe, appears robust,” wrote Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economics research at HSBC. “But it is China that’s been the main engine for growth across the region – and as it sputters, Asian economies will lose much of their torque.”

HSBC analysis showed Asia-Pacific economies from South Korea to New Zealand far more correlated to changes in China’s growth than they were to changes in U.S. or European GDP.

For every percentage point China added to its growth, trade powerhouse South Korea reported about 0.7 of point of additional growth, the bank’s economists said.

South Korea was by far the most sensitive to changes in Chinese growth, according the analysis, followed by exporting nations Thailand and Taiwan.

An anticipated Chinese slowdown has already prompted Citi analysts to downgrade growth projections for economies in the region, including South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam.

A Reuters Corporate Survey last week showed a majority of Japanese firms were concerned that a slowdown in China, Japan’s largest trading partner, would affect their business.

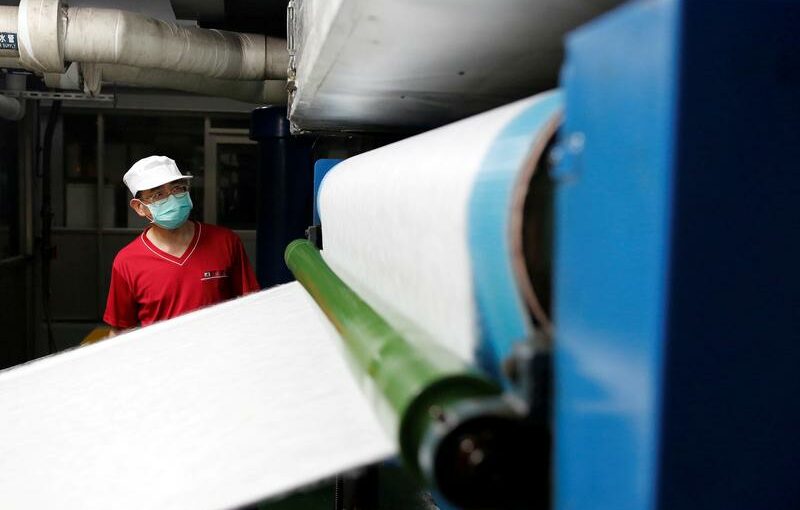

The slowdown is being felt across most of China’s economy, from the retail to factory sectors, which posted its weakest output growth since the start of the pandemic.

China’s auto sales slumped 19.6% in September from a year earlier, industry data showed last week, falling for a fifth consecutive month amid a prolonged global shortage of semiconductors and the power crunch.

Similarly, sharp declines in new construction starts in China’s property market, due to a regulatory crackdown, loom as risks for exporters of raw materials, such as Australia.

Iron ore prices have nearly halved since hitting a record in mid-May, with demand hurt by China’s steel output curbs and the property slowdown.

Last week, mining giant Rio Tinto downgraded its 2021 iron ore shipments forecast, mostly due to tight labour market conditions in Australia, but it also warned of headwinds from China’s regulatory crackdown.

‘STAGFLATION’

Despite the risks from China, analysts say Asia will be able to prevent a precipitous collapse in domestic demand, as improved vaccination rates allow countries in the region to shake off COVID-19 restrictions.

Similarly, Chinese demand for some goods, such as fuel and food, remains firm. That means for now, central banks are unlikely to swerve from their general shift away from crisis era monetary settings.

Singapore last week tightened its monetary policy.

Beyond the broader demand shock, complications for economies in Asia and elsewhere could come from worsening supply-side problems in China, such as the power crunch.

So far, China’s manufacturers and exporters have yet to significantly pass on higher costs caused by supply shortages of everything from coal to semiconductors.

But analysts warn the situation around inflation is fluid.

While weaker demand could relieve pressure on prices, supply chain bottlenecks, if unresolved, could create a “stagflation” nightmare in which surging prices are accompanied by stagnant growth.

“I think it could potentially be a bit of a double whammy now. Because China is one of the economic engines for the region, any slowdown can affect the demand for regional goods and services,” said Selena Ling, head of treasury research and strategy at OCBC Bank.

“Secondly, the ongoing power crunch, in all likelihood, policymakers will prioritise home (use) for winter demand over industrial activity. So that could exacerbate global supply chain disruptions.”

Source: Read Full Article