India can claim that its twin principles of equity and “common but differentiated responsibilities” found their way into the Paris climate change summit’s 31-page text.

However, the omission of historical responsibilities, implying the build-up in the atmosphere of 165 years of greenhouse gas emissions from industrialised countries, is a body blow to the notion of climate justice, sums up Darryl D’Monte, reporting exclusively for Rediff.com from COP21.

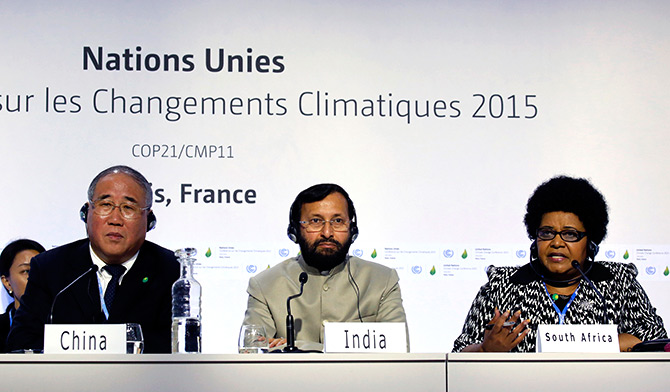

Even the casual observer will notice that India isn’t being overly enthusiastic about the outcome of the UN climate summit in Paris. Environment Prakash Javadekar has been stressing that it could have been more ambitious but in the interests of a consensus, it went along with other nations.

India can claim that its twin principles of equity and “common but differentiated responsibilities” found their way into the 31-page text. However, the omission of historical responsibilities, implying the build-up in the atmosphere of 165 years of greenhouse gas emissions from industrialised countries, is a body blow to the notion of climate justice.

In one stroke, it places countries at par with each other, though nominally observing “respective capabilities and national circumstances”. From George W Bush Jr to Barack Obama, American presidents have been dead-set on China and India not being classed as developing countries and therefore not cutting their emissions. After Paris, a US negotiator said that differentiation in climate responsibility was now forward-looking as opposed to backward-looking.

China’s and India’s fast growth rates as “evolving economies with emerging trends” are being cited to exclude them from developing countries. This has always negated the fact that all BASIC countries — Brazil, South Africa, India and China — also have large populations which are poor, which is why they all belong to the older alliance: G77 (now actually 137 countries) + China.

In Paris, Todd Stern, the chief US negotiator, mentioned how China was providing $3.1 billion to developing countries as climate aid and implied that other emerging economies should “expand the donor base”. This is particularly problematic for India which has the largest number of poor people in the world.

A few years ago, the UN Development Programme, using a new multi-dimensional poverty index in its annual human development report, pointed out how eight Indian states had more poor people in absolute terms that the 26 poorest sub-Saharan African countries combined.

On the eve of Paris, three independent Indian institutes released a report which showed that India would itself need over $1 trillion by 2030 to tackle the adverse impacts of climate change. It noted that 800 million in 450 districts were already experiencing summer temperatures which are 2?C higher than normal. Between 2016 and 2045, India as a whole would face an average temperature rise of 1-1.5?C, which is the target set in Paris for the globe for 2100.

Since Paris was an international summit, it was important for India to continue emphasising the need for equity in every respect — in principle as well as in implementing these objectives. But different countries have different ideas of what equity comprises.

Obama could claim, quite arrogantly, that the accord was “a tribute to American leadership… [and] Over the past seven years we’ve transformed the US into the global leader in fighting climate change”. As anyone who is familiar with American lifestyles knows, this is overblown rhetoric. It is the US which is the world’s laggard on the climate front.

As the Delhi-based research group, the Centre for Science & Environment, cited in its incisive recent document, ‘Capitan America’, the US’s INDCs of reducing emissions by 26-28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2025 pales into insignificance to just 15 per cent if measured against 1990 levels as prescribed under the Kyoto Protocol of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The EU has pledged to reduce its emissions by 40 per cent below 1990 levels by 2030. But the US refused to sign the protocol because it quantified each rich country’s emission reductions and prescribed financial penalties for failing to do so. All that remains of the protocol today is the continuance of a carbon market where industrial countries can buy emission reduction certificates from developing nations where it is cheaper to do so than at home.

India has every right to call for equity in all countries’ commitments, not least the US which ceded its rank to China as the world’s biggest polluter only in 2010. This is at the level of international diplomacy.

However, at home, India can’t seek shelter behind the fact that there are 300 million who have to make do without access to electricity. For that matter, it doesn’t much refer to the 800 million who have to use wood and farm waste to cook with.

This causes two million premature deaths in the country every year, not to mention the terrible scourge of a range of airborne diseases, affecting women and children primarily.

Greenpeace released a report in 2007 accusing India of “hiding behind the poor” where it mentioned that its per capita emissions of 1.7 tonnes per year masks the gross inequalities within the country. If the top percentages of Indians by income were analysed, these would approximate Europeans’ emissions of 4-7 tonnes per annum.

In many respects, the energy required for cooking food is even more important than that of electricity. One can do without a light at home, but cooking is indispensable. Since firewood figures at this level in the realm of “non-commercial” energy, little attention has been paid to it.

Just as rights to food, work and education have been prescribed in the country, there should be a right to energy, which includes electricity. At Paris, Indian negotiators were quick to point out, quite correctly, that merely enabling a person to light a bulb at home or providing a socket to charge his cell phone was insufficient. Indians are now getting aspirational and are demanding a higher standard of living, something they witness in the bigger cities.

Image: Prakash Javadekar, minister of state for environment, forest and climate change (centre), with Xie Zhenhua, special representative for climate change of China (left), and Edna Bomo Molewa, minister of environmental affairs of South Africa, at a news conference during the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) at Le Bourget, near Paris, France, December 8, 2015. Photograph: Jacky Naegelen/Reuters.

Senior journalist Darryl D’Monte reported from the Paris climate change summit exclusively for Rediff.com.

Source: Read Full Article