This summer’s big New York City performances have lugged considerable metaphorical baggage, from the giddy, vaxxed-but-maskless return of the Springsteen on Broadway concert during the pre-Delta shine of June, the resurgent Covid delays of Shakespeare in the Park and finally last night’s aborted, starry concert in Central Park, when the sky itself seemed to tell pop’s mightiest stalwarts, eh, not quite yet.

Tonight’s performance at the August Wilson Theatre of Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s thrilling Pass Over, the first Broadway play of the post-shutdown era, will, happily or not, carry some weighty burdens of its own. Forget the random media reports of the production’s maybe, maybe-not financial struggles – seriously, who isn’t struggling financially these days?

Equally unfair is asking Pass Over, or any other single Broadway production, to somehow reflect or embody all that’s happened in our world over the last 17 months of illness and death, Covid and George Floyd, to somehow be thoroughly of Aug. 22, 2021, with no trace of the Broadway that closed March 20, 2020.

Watch on Deadline

Those burdens aside, the show’s producers made a smart choice in pushing Pass Over to the front of Broadway’s opening night. The play, a canny, streetwise meld of Beckett and the Bible suffused with magic realism and even an apparent fondness for ’70s sitcom The Jeffersons and its famous “Movin’ On Up” theme song, does indeed reflect this moment in time. With its lingering doubts and braveries, its dramaturgical sharpness giving way to a messiness that feels somehow unfinished, Pass Over is a forthright work of serious intent and comic panache, beautifully acted by its three-person cast and powerful in its angry, hopeful voice.

And a note to anyone who has seen Spike Lee’s 2018 film adaptation, Pass Over now has a different ending. A better ending. But more about that shortly.

The play begins as two Black men greet the day on a mostly barren urban street corner. Longtime friends Moses (Jon Michael Hill) and Kitch (Namir Smallwood) while away the long, Ground Hog Day hours teasing and reassuring one another, arguing and making peace, and forever dreaming of their own promised lands – Moses is fully aware that his name is both passport and yoke. In one game the two friends play repeatedly, each lists 10 things that will arrive with a promised land beyond their suffocating city block. Moses’ list includes collard greens and pinto beans the “way reverend missus used to make ’em,” his old bright red Superman kite, soft sheets and a woman to share them with. And he wants his brother, back from the dead.

Neither playwright Nwandu nor director Danya Taymor waste any time establishing the Waiting for Godot-ness of it all. Moses and Kitch complain about their aching feet, just like those classic existential tramps Vladimir and Estragon, and both plays live in worlds between resignation and desire. As Moses dreams of escape, Kitch responds, “Maaaaaan how da fuck you spect we fixta git up off dis block?”

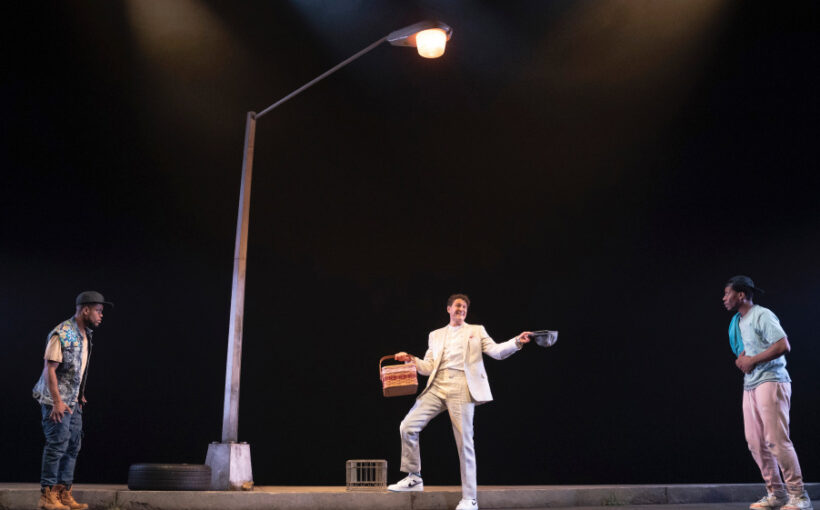

That dialogue spelling, not incidentally, is taken directly from the script, and the characters’ manner of speaking, complete with frequent use of the N-word, will become a significant plot point with the arrival of a third character, the mysterious Mister (Gabriel Ebert), a white man dressed in summer linen and toting a bottomless picnic basket on his way to mother’s house.

Mister, whose real name replaces that “i” with an “a,” is certainly Pass Over‘s riskiest dramaturgical gambit. With an impossibly sunny demeanor, abundant food to share, a ukulele to strum and a vocabulary that gets no rougher than “gosh golly gee,” the seemingly benign Mister isn’t so much human as idea, or maybe demon, a specter from the plantation or maybe just one of those butt-of-the-joke white characters who served as foil to George Jefferson.

In any case, Mister’s interlude leaves Moses and Kitsch with an idea, and a dangerous one: Perhaps if they mimic his style, taking on his manner of speaking and genteel ways, they too can escape the world’s wrath and police attention.

Soon enough, their experiment is put to the test, when a cop (also played by Ebert), arrives on the corner. The experiment works until it doesn’t.

In the original stagings of this play – as seen in Lee’s 2018 film – it was Mister who returned to wrap up loose ends, including Moses’ life. That conclusion was both shocking and expected, blunt and without hope. Without spoiling the new ending, Nwandu has concocted a more fantasy-like approach, embracing an Afrofuturistic style and a continuation of the magic realism that has already made sporadic appearances, and while there will be blood, its source might surprise. Even the cop is offered a chance at redemption as the set, designed by Wilson Chin, transforms from the stark urban purgatory – presided over by a streetlamp that looks more like the gallows in a game of Hangman – to something altogether more pastoral, more promised.

It’s a better, if still not altogether satisfying, ending, as the play’s infusion of the fantastical never entirely gels. The vaudeville characterization of Mister/Master and the nightmare stereotype of a cop named Ossifer are defendable dramatic choices – the Black men are the people of this play, and they share the stage with ghosts and shape-shifting terrors.

But if the promised land of the movie’s ending was death, that ultimate pass over, here the rising seems more spiritual, a triumph over racism, with blunt mea culpas and radical forgiveness. In other words, complete immersion into paradise made from desire and sheer will. In its own way, this new angle feels only slightly less abrupt than the old way’s bloody gun shot, and there is a very fleeting coda of temptation and doubt – a moment that director Taymor might consider extending for just another beat or two. Even in the new world beyond care, we’d all be wise to remember that neither human evil nor human susceptibility can be wished away.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article