Experts disagree with the idea and the RBI, which has the sole right to print money, is not comfortable with it as well.

Nobel Laureate Abhijit Banerjee, in May, said India should print money to finance the government’s fiscal deficit, offering advice for an economy devastated by a second wave of Covid-19 infections.

Experts disagree with the idea and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which has the sole right to print money, is not comfortable with it as well.

Here are key things to know about printing money to finance deficit.

How money is printed

The RBI has two ways to infuse money in the system.

One is by buying dollars from the market while infusing rupee liquidity in return.

The second way is to buy government bonds from the secondary market and pump in liquidity.

These are two generic ways to infuse money.

The central bank expands its balance sheet through foreign currency assets when it purchases dollars.

When it buys government bonds, the expansion is made by buying domestic assets.

What is deficit financing by printing money

Buying bonds from the secondary market to infuse liquidity is an indirect way of financing the government’s fiscal deficit.

There is a direct way as well: when the government privately places bonds with the RBI. India used this system in the mid-1990s when the government placed ad-hoc treasury bills with the RBI.

Fiscal deficit was automatically monetised through ad-hoc treasury bills, which were issued by the RBI on behalf of the Centre to itself at a fixed rate.

RBI is the government’s merchant banker, managing its fund raising programme.

It issues government bonds to the banks to raise the funds.

Simply put, RBI subscribed the bond issues it hade made.

When Chakravarthi Rangarajan was the RBI governor in 1997, the policy of automatically monetising the government’s fiscal deficit was discontinued.

Why direct financing of deficit is being demanded now

There is again a debate whether India should undertake automatic monetisation of the deficit, given the hurt to its economy.

Some former central bankers have supported such a move.

It is an unconventional policy also known as helicopter dropping of money: a term coined by American economist Milton Friedman in 1969.

India’s GDP contracted by 7.3 per cent in 2020-21, the first time it happened so in 40 years.

Various quarters want more money pumped into the economy to revive GDP growth.

The RBI took a growth-supportive stance after the pandemic broke out last year, reducing the repo rate by 115 bps between March and May of 2020.

Further interest rate cuts were not possible after that though: repo rate is at 4 per cent, while average retail inflation in FY21 was 6.2 per cent and for FY22 it is projected at 5 per cent.

The RBI opened a liquidity tap in April–namely Government Securities Acquisition Programme–to buy government bonds from the secondary market.

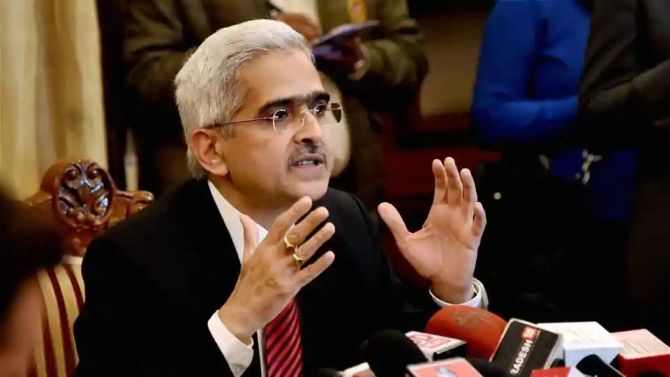

RBI governor Shaktikanta Das recently announced the second version of the G-SAP.

G-SAP 1.0 was worth Rs 1 trillion; G-SAP 2.0 will be of Rs 1.2 trillion and it will buy state government bonds as well.

Das also announced keeping the repo rate unchanged.

What are the drawbacks of such a move

There is an argument that the central bank is printing money and buying bonds from the secondary market, so the objective of economy stimulus is fulfilled.

Hence, there is no need for a direct purchase on bonds.

“I am not in favour of such a move that is private placement of bonds to RBI by the government,” said Indranil Pan, chief economist at Yes Bank.

“The RBI, through its balancesheet and its participation in the secondary market, is doing exactly that (pumping money).

“Quantitative easing…open market operations etc, is happening in any which way.

“The whole reason why the private placement was taken off was to guide the government towards a discipline towards its borrowing and fiscal deficit,” Pan told Business Standard.

There is apprehension that such direct financing of the deficit will hurt fiscal prudence.

The country has repeatedly pushed back its target of achieving 3 per cent fiscal deficit.

Pan said that direct monetization of the deficit can have a bearing on maintaining fiscal discipline.

“Till the point in time RBI, with all the tools, was able to cap the yield movement – the purpose was achieved,” he said.

RBI’s view on the issue

The central bank has managed the borrowing programme well.

It managed, in the last financial year, a government borrowing of Rs 12.8 trillion rupees, at rates lowest in 16 years.

The government has announced, for this financial year, a borrowing of Rs 12.05 trillion.

The figure is likely to rise due to an anticipated shortfall in GST revenue collection.

The yield on 10-year government bond has been hovering around 6% since G-SAP 1.0 in April, allowing to RBI say the borrowing cost is under check as bond yields are under control.

Governor Das made this point recently.

“Regarding the printing of notes, the central bank has their own models and their own assessments.

“The central bank, with regard to printing notes, takes the decision on the basis of many complex factors, relating financial stability, inflation, exchange rates,” he said during the post-monetary policy interaction with the media.

“RBI has been managing the borrowing requirements of the states and centre very successfully.

“Last year the borrowing rates were lowest in 16 years.

“This time also RBI has taken measures in terms of GSAP 1.0 and GSAP 2.0.

In addition to Rs 60,000 crore auctions under GSAP 1.0 done so far, RBI has injected another Rs 36,000 crore.

“The borrowing is going on smoothly,” he said, indicating his views on the issue of automatically financing the government’s fiscal deficit.

Source: Read Full Article