We live in hope that India and its airlines might finally grow up, notes Anuli Bhargava.

As we head into what is being loosely referred to as the third COVID-19 wave, India’s aviation industry is heading into a third wave of its own.

This wave will be defined by three or four trends that will redefine and alter the landscape for Indian aviation after the pandemic, a game changer for the sector globally.

India’s short aviation history or the first wave began in the 1950s with the birth of Air India and Indian Airlines, the two publicly-owned and -run carriers.

Air fares were exorbitant and flying was a luxury only a few could afford. Back in the day, it was not uncommon for passengers on flights to know each other by name.

This changed once the sector was opened to private scheduled operators and airlines such as Damania, East West, ModiLuft and Jet Airways took to the skies.

Of the lot, only Jet left an imprint on the Indian passenger’s psyche and for many years, the efficiently run full-service carrier (FSC) ruled the domestic skies, with Indian Airlines as its poor cousin. The total number of aircraft in Indian skies amounted to 120-130.

In 2004-2005, the second wave began. Sparked by Air Deccan, India’s first low-fare airline, this marked the beginning of what was an explosion of air travel by many who couldn’t afford it previously.

Soon after, Indian aviation embraced the low-cost revolution, and irrational fares meant larger numbers of the aam aadmi experiencing air travel for the first time.

A clutch of Indian carriers jumped in, many failed but the market grew steadily.

By 2014 or so, the number of aircraft in Indian skies was 370-380. The years 2005 to 2014 (barring some aberrations) saw heady growth in the number of air travellers, within India and overseas.

From 2014 to 2019, traffic growth remained steady and the total number of aircraft operated by the Indian carriers crossed 700 by the end of 2019.

It was the pandemic that dealt a lethal blow to these glorious 15-odd years.

In March 2020, traffic hit a standstill. The net effect can be seen in the drop of aircraft registered with the Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA): On December 22, 2021, it was 658 in total.

Moreover, the number in use was lower at 506, indicative at least partly of the sharp knock to demand.

It is now post-pandemic and after the sale of Air India that experts, analysts and those vested in the industry see the next wave happening.

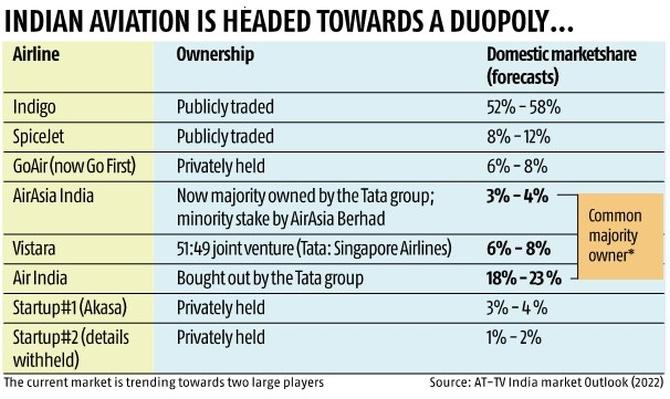

Government and industry sources estimate that by 2028-2030, the total Indian fleet will cross 1,000 aircraft, but the cocktail and composition of airlines are likely to be altered.

Two or three distinct trends are expected over the next decade or so.

One, growth will be slower for a host of reasons and may not return to 20 per cent levels although it will stay robust.

Many in the sector expect a 9-10 per cent CAGR over the next 10-odd years.

In the coming decade, a greater segmentation of the market is expected. The blurry lines between FSCs and low-fare airlines will sharpen, albeit gradually, probably to the relief of the former.

In mature markets, such as the US and Europe, those who opt for full service are happy to pay for it and there is little overlap between FSCs and low-fare carriers.

In general, competition should become saner and two distinct markets should begin to emerge.

This may take longer in India than it did in many developed markets, but it will get there.

A second clear demarcation could well be in the outlook of airlines.

Many argue that the new Tata airline — if it gets its act together — may emerge as India’s answer to Emirates, Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa, a true international carrier that recovers some of the traffic lost by India over the years to foreign carriers.

This lost traffic is a matter of much debate especially in today’s atmanirbhar environment but in the absence of these foreign carriers stepping in to transport aspirational and increasingly mobile Indians, passengers would have paid through their noses if seats were available at all.

Air India alone was not going to be able to cater to the burgeoning demand, especially since forces combined to ensure that the airline didn’t order new aircraft for almost 15 years.

It would be fair to say that the bureaucrats and politicians of the time dug Air India’s grave through their mismanagement.

In fact, Air India and Indian Airlines loyalists argue that had the merged entity ordered more A320s and managed its affairs better, IndiGo would never have emerged as the market leader.

This brings us to IndiGo and what it might be currently contemplating.

Few airlines around the world have succeeded with running a mish-mash of a domestic and international airline under the same umbrella.

The danger of losing the plot when a wide-body aircraft is introduced in a predominantly narrow-body operation is well known and acknowledged globally.

So, will the market leader stick to the core and consolidate its domestic operations that will only grow with time and remain content with international routes that can be flown with the present fleet? Many think it might.

The addition of the A321XLR, expected in 2024, will give IndiGo much more range and allow it to cover many more regional destinations in any case. It has a good thing going: Is this steady boat worth rocking?

Last but not least, the next decade is expected to finally lead to a clean-up of the sector: More professionalism, more rational fares, capacity additions that reflect real demand, healthier balance sheets and cash balances and better governance all round.

In the process, it is argued many less-than-desirable practices will slowly vanish.

This would be the most awaited and desirable development. We live in hope that India and its airlines might finally grow up.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article