Though COVID-19 will wreak more damage to the finances of the Indian population, the insurance sector is unlikely to get hurt.

Subhomoy Bhattacharjee reports.

Far less people ventured out with their cars on the Indian streets in 2020.

This year, too, with lockdowns spreading fast, the vehicles will remain off the streets for a long time.

This is good news for the Indian insurance sector because there will be far fewer claims to report.

India’s largest non-life insurer New India Assurance actually ended up with a small profit in its motor portfolio of Rs 87.4 crore (Rs 874 million) in the second quarter of FY21 — a first after a long time.

In the same period of FY20 it had made a loss of Rs 272.8 crore (Rs 2.728 billion).

Motor, the second largest selling non-life insurance product, is a good reason non-life insurers look back to FY21 with pleasure.

So do health insurers, the largest selling non-life product, despite COVID-19.

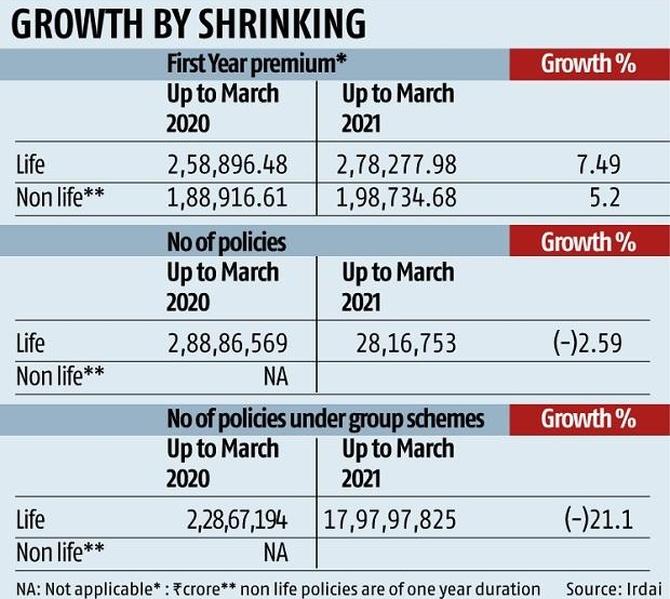

The industry grew at a healthy clip of 5.2 per cent. The numbers are quite a contrast with the almost nil growth rate for non-life insurers abroad.

“Claims have certainly not increased as a percentage of the insured pool. Rather, I suspect, people have become more regular with their premiums,” said P J Joseph, former member of the sector regulator, Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (Irdai).

He is partially correct. The aggregate first year premium, the usual common top-line metric, grew 7.49 per cent in FY21 for life insurers.

Note, however, the number of life policies have dipped, as poorer people closed policies to pay for more immediate needs, yet the total premium booked has risen.

By staying off mass products, the insurance companies have done their balance sheets a good service.

Ayushman Bharat, the Government of India’s ambitious programme to provide some health insurance cover to all Indian population, particularly the poor, was launched in 2018. By now most insurance companies have left the tent.

As a result, there will be very little impact on them of the current medical emergency.

Of the 32 states and Union Territories that have signed on to Ayushman Bharat, only in six major states, such as Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Punjab, do insurers have some exposure. The rest are borne on state budgets.

Consequently, in FY22, though COVID-19 will wreak more damage to the finances of the Indian population, the insurance sector is unlikely to get hurt.

A large percentage of those who die will not have a life cover.

A joint finance ministry-Life Insurance Corporation study last year discovered less than 20 per cent of the dead had a life cover.

In health, too, the coverage is only now beginning to pan out and will take years to reach a critical mass.

Unlike banks, whose bad loan baskets mount in a bad year, insurance companies in India have had a golden run.

Life insurance premium in India increased 11 per cent in the past two years, the non-life sector did even better.

Compare this with the global total insurance premium which increased by just 2.34 per cent in 2019.

The world’s largest reinsurance company Swiss Re expects total global direct premiums written will reach pre-crisis levels only at the end of 2021.

This was before India and other markets were hit by the second COVID-19 wave.

For the 24 life insurance companies and 34 non-life companies in India, some of the fast clip growth is simply making up for the years of under-penetration of the market (percentage of insurance premium to GDP).

It was 2.7 per cent in 2001 climbing to 3.76 per cent in 2019. The global average is 7.33.

Of course, the states, too, are somewhat at fault. They are reluctant to pay premiums for Ayushman Bharat or for crop insurance, but are more than eager to demand larger claims.

As a result, the insurance companies are happy not to play any risky games to extend the reach of the total insured pool. This has created a cozy club.

The existing companies chase a few well-defined portfolios and are happy with the profits they generate.

The private sector life insurance industry did see a 13 per cent dip in their profits to Rs 5,016 crore (Rs 50.16 billion) in FY20 compared to FY19, but the non-life sector made up with an almost 12.4 per cent equivalent rise to Rs 4,037 crore (Rs 40.37 billion).

:The Indian insurance market is still a savings-oriented market. Customers are not opting for protection products such as term insurance,” said Shashwat Sharma, partner at consultancy firm Kearney.

For instance, life insurance companies push a lot of loan-linked products. “Those have very high margins,” he said.

What does this restricted growth do for companies like Fedo, which is trying to bring data analytics into insurance? Do insurers need those products, when the existing basket is already a cash cow?

“Leading online insurance aggregators have made some inroads into sales, but the majority of the sales are still driven by your friendly neighbourhood insurance agent,” said Prasanth Madavana, co-founder and CEO, Fedo.

In FY21, according to Joseph, the rush to take out health insurance policies and the revision in premium for commercial vehicles have improved the receipts for the non-life insurers.

Group policies are the preferred option for non-life insurers to expand their business, said Sharma.

There are two telling pieces of data with Irdai. The first of these is the number of life insurance offices.

Those have almost remained flat. But they begin to look worse if one cuts out the presence of LIC.

The percentage of offices of the private sector companies in Tier I towns is close to 80 per cent.

Even if one argues that the presence of brick and mortar branches is not needed for selling insurance products in the digital age, it is surprising those offices should be mostly in the big towns.

People in cities would be more digital savvy. A smart insurance approach should instead be to relocate them in smaller towns. But, the concentration of these offices has rather risen in the largest towns of India.

The second data is about the number of life insurance policies sold to women in India.

Again, Irdai data shows the share of women buying these policies has decreased to 32 per cent in FY20, a sharp drop year-on-year from 36 per cent in FY19.

If one nets out the policies sold by LIC, the numbers dip to 27 per cent. Insurance coverage seems to be excluding the poor and the women in large swathes.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article