Stuck at home during lockdown, you’ve spent a lot of time on your phone.

With schools shut and kids learning from the living room, you may have used it to buy more devices.

You might have upgraded the TV, too, what with all the time they were spending streaming in the evening.

At least they have those wireless headphones, without them you wouldn’t be able to hear yourself think.

That new fridge was worth the money though, given the amount of traffic it’s seen.

Same goes for the smart kettle that replaced the old steamer when it finally gave out.

With the shops closed more than they were open, you’ve lost count of the number of home deliveries.

There’s another one due shortly, according to that ping from your new watch.

Thank goodness one of the first lockdown purchases was that clever doorbell which lets you see who’s coming.

The one thing that’s not been replaced is the car outside. No surprise really, given how little it’s been driven in the last year, but when it does go, wouldn’t it be nice if the new one was electric…

This vision of domestic digital consumption is not one everyone will recognise, but it is common enough to have placed a premium on the element every one of these products has in common: chips.

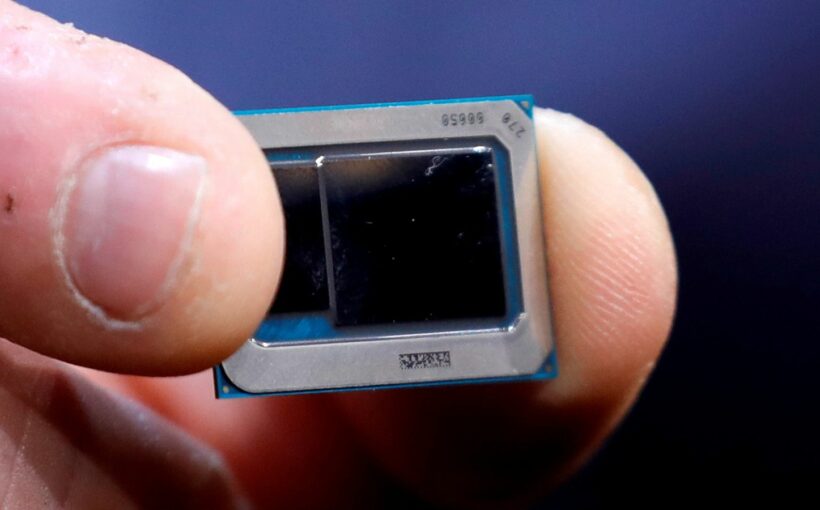

These tiny components made of conductive material, usually silicon, carry the microscopic processors that keep our digitised, connected world moving.

They are in almost everything, from the device on which you are reading this article, to the satellites that helped the delivery guy find your house.

But in recent months, a global shortage of chips – or semiconductors – means we may not be able to rely on the goods we buy turning up with such certainty.

Across multiple industries, from electronics to automotive, there is a rush to secure limited supplies of the most crucial component in modern manufacturing, and shortages are already beginning to bite.

This week, BMW-Mini became the latest car manufacturer to be affected, announcing a shutdown to production at Cowley, Oxford.

Hitherto the only car plant in the UK that has kept running throughout the pandemic, it follows Jaguar-Land Rover, which has paused production at two of its factories.

Modern vehicles have multiple chips to control everything from engine management to automatic windscreen wipers, giving this tiny part the power to bring giant production lines to a halt.

Their importance is only going to increase as we shift to electric vehicles which require up to three times as many as internal combustion engine models.

Ford in the US has forecast that the chip shortage will cut vehicle production by 50% between now and June, costing it 1.1 million vehicles and $2.5bn.

In the UK, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders says the sector’s recovery post-pandemic will be hampered by the struggle to manage the “global semiconductor shortage”.

Even the world’s most valuable company is not immune. Apple‘s success is built on sales of its hardware, the smartphones and tablets that rely on chips, and chief executive Tim Cook has warned that production of some of its products may be affected.

Announcing a 54% increase in sales in its latest results, the company said it had relied on using its buffer stock of semiconductors to meet demand, and anticipated sales of iPads and Macs would be $3bn to $4bn lower in its third quarter than would be the case without supply issues.

Mr Cook said the company was competing with other industries not for ground-breaking chips that give Apple an edge, but older “legacy node” technology used to manage battery life and other elements of the phone.

“Most of our issue is on licensing those legacy nodes, there are many different people not only in the same industry, but across other industries that are using legacy nodes,” he said.

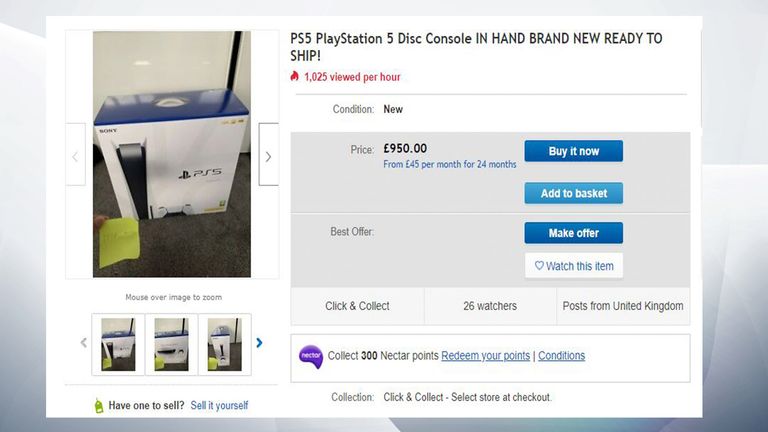

The chip issue has also been an element in supply shortages of the new Xbox and PlayStation gaming consoles and, as for every other industry, there is not likely to be a quick solution.

Chip design is a global business led by the US in which the UK has been prominent, largely through Arm Holdings, founded in Cambridge but currently owned by Japan‘s Soft Bank and in the process of being sold to America’s Nvidia.

For production, however, the world depends largely on Taiwan and South Korea, both of which have long lead-in times and enjoy fierce competition for capacity.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the industry giant, followed by South Korea’s Samsung, and they and every other manufacturer have been swamped by a variety of issues.

It’s not just lockdown demand for electronics that has squeezed supply.

The contraction in car production has been followed by a quicker than expected recovery, catching producers out.

Natural forces and geopolitics have played their part, too. Tension and trade sanctions between China and the US, including pressure on Huawei, have seen a spike in demand from China.

The weather has played its part as well. Chip production uses high volumes of water, and drought conditions in Taiwan have hampered production, as did February’s deep freeze in Texas, causing power cuts that hampered production at semiconductor plants, including one run by Samsung, well into March.

Meanwhile, an explosion at a Japanese Renesas Electronics plant in February also exposed the vulnerability of pressurised supply chains to isolated events.

For consumers, the impact for now may be an irritating delay to items that you might be able to live without. But now we have chips with everything, that list is getting smaller every day, and ultimately, we may be the ones who pay.

Source: Read Full Article