By Adele Ferguson and Naomi Shivaraman

Former Aus Streaming Ltd employee Stephen Helberg unpicks the web of companies.Credit:60 Minutes

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

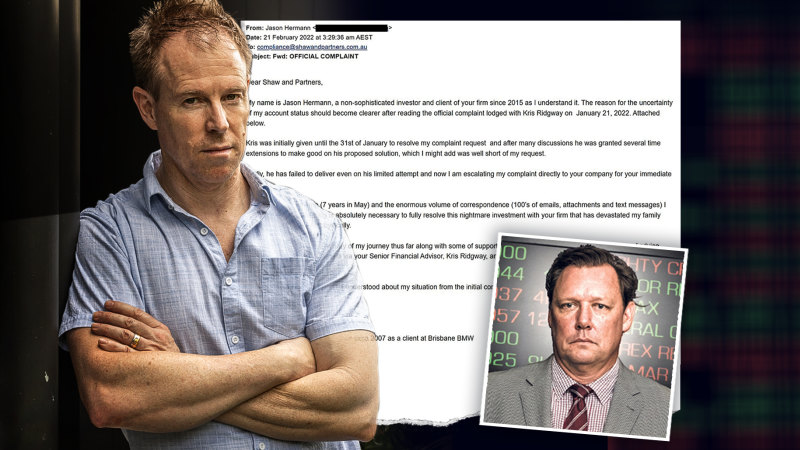

Jason Hermann had had a gutful. His life was in turmoil after years of lies and excuses. He had a drink, sat down and composed an email that would ricochet inside one of the country’s biggest wealth managers, Shaw and Partners, exposing one of its senior financial advisers, Kris Ridgway, and a global financial scandal.

“I and my family have had enough, we are exhausted financially, mentally and physically,” he wrote to Shaw on February 21 last year. “Maybe Shaw and Partners have the patience required for the promised return on this investment (if it is in fact legitimate) but my family do not.”

Hermann was referring to a global investment scheme, supposedly backed by billions of dollars in assets, that is still in play and that has embroiled potentially thousands of investors, who signed with advisers such as Ridgway, believing they were investing in companies that were about to be listed on an international exchange and make them a fortune.

The stocks still haven’t been listed eight years later and, when Hermann tried to sell just a small parcel earlier this year, there were no buyers.

It was a watershed moment that revealed the shares were worthless.

“It was like some type of significant crime had been committed and you’d just turned up at the police station. It’s like, ‘Help’,” Hermann tells a joint investigation by The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and 60 Minutes.

Four days after the email, Ridgway was sacked and reported to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. He had circumvented Shaw’s compliance systems over eight years and had put up to 100 investors into unauthorised products and had taken secret commissions, which is illegal.

Next to his desk was a filing cabinet that included bank account details, records of commissions, share transfers and other incriminating documents of companies that Shaw had never heard of.

Jason Hermann wrote to Shaw and Partners, exposing Kris Ridgway.Credit:Paul Harris

Ridgway jumped in his car and drove from Brisbane to Sydney, leaving his wife and three children, and stayed with his associate David Sutton for a few weeks, discussing how long it might take for the negative publicity to blow over.

Inside the ‘spiderweb’ of companies

Stephen Helberg was not surprised. He had come to a similar conclusion about the companies in 2016, shortly after joining Aus Streaming Limited, a mining services company that was part of the empire, as executive chairman.

Helberg, an auditor of 40 years, who had previously worked in senior roles at Rio Tinto and CIMIC as well as holding partnerships at KordaMentha and Ernst & Young, had been headhunted by two men central to the scheme, England-based Andrew Turner and Australian businessman Sutton.

But nothing prepared him for the elaborate spiderweb of companies he found himself in when he started peeling back the inner workings of Aus Streaming Ltd, which included Sutton as a director of the board.

Alarm bells started ringing within months of Helberg joining, when he became suspicious that the purported assets of $138 million on the Aus Streaming balance sheet could not be found.

He contacted the company’s external auditors, Nexia, which had audited the accounts and had told him it had relied on independent valuations. “It turned out that those valuations were not independent,” Helberg says. He says that based on a PwC investigation, the valuation was prepared by a business that operated from the same address as Sutton.

Helberg says as he started to hunt for the assets, he uncovered a web of interconnecting companies, most registered in tax havens, claiming to have a total balance sheet of more than $6 billion.

Stephen Helberg quit Aus Streaming when he could not locate the company’s assets.Credit:Simon Schluter

In 2017, he quit and called in the lawyers. The company owed him $250,000 in unpaid salary. Months later it was wound up.

He formed the opinion that it was a global organisation set up to “mislead investors”. “Not only investors, but the external auditors as well.”

Until its collapse, Aus Streaming was part of the ASAF Capital Group, a British Columbia company Ridgway and Sutton and other advisers put investors into. Ridgway received secret commissions paid directly into his bank account from McFaddens, a business run by Sutton.

Helberg believes more than 2000 investors have been caught in the scheme, which includes ASAF and other companies such as Steppes and Trinus, all linked to Sutton and Turner and all spruiked to investors by Ridgway and other financial advisers.

Kris Ridgway, top, is questioned by his former employer, Shaw and Partners, shortly before his sacking.

The report that laid out the problem

In 2020, PwC’s forensic accountants spent 12 months trying to find the assets in Aus Streaming but failed, partly due to the complexity of the companies.

But the report by PwC, commissioned by the courts in 2020 as special purpose liquidators to find the assets on behalf of creditors, lists a series of potential breaches of director duties, conflicts of interest and questionable conduct.

It spent the year trawling through records and visiting offices that had been left vacant, but it couldn’t find assets that had any value. Nor could it find the independent valuer of the assets, ECB, noting that correspondence was ignored, the address was unknown and the website address defunct. It said Turner didn’t provide contact details. But it said an internet search conducted by PwC linked the company’s number to McFaddens & Co Group, an advisory business with a base in Dubai linked to Sutton, which was also located at the same address as a consultancy group run by Turner.

It found a “deliberate opaqueness in the structure, management and business activities of what appears to be a large group of interconnected organisations registered in a number of jurisdictions spanning the globe”.

Turner, who says he has worked with Sutton on projects since 2014, disputes the PwC report.

“Aus Streaming was going to go public via a reverse merger, which, due to circumstances beyond the company’s control, it did not complete,” he says.

“The report by PwC was arranged by a conflicted party. A separate independent report that was not conflicted came up with a very different conclusion to PwC and did find value in the assets.”

He says shares have not been listed because “unfortunately, due to Covid and the subsequent financial markets turmoil of the past 18 months, the market for IPOs has dried up with London recording its worst market for IPOs for 14 years”.

Investors, he says, can sell their shares on a secondary placing market.

Sutton says his legal advice is not to comment.

The support group

Helberg wasn’t prepared to let it go. He became part of a support group, which included Hermann and another investor, Darren Walker, to share stories and information in the hope of getting to the bottom of what was going on.

From the outside, Sutton and Turner didn’t appear to miss a beat. It looked like business as usual.

On April 29, 2022, two months after Ridgway had been sacked and four weeks after this masthead exposed the scandal, investors, including Walker, received an update about one of the companies in which they had invested, Trinus Private Equity, from the McFaddens’ email address. It said Trinus “is now in a position to commence with its public listing on the Euronext Stock Exchange”. It said the process would take 90 to 120 days and a further update on the listing would occur in May 2022.

David Sutton near his home in Sydney.

Investors weren’t buying it. One New Zealand-based investor, who had lost money from a previous investment, wrote, “Andy [Turner], what we need to understand is when do we get liquidity (return of cash) and extract ourselves from this perpetual investment web? From where I sit right now, I just want my $400,000 investment funds back as I have advised continuously to David Sutton, over many months.”

Then, on June 25, Turner wrote to one of the investors saying: “I have been in hospital undergoing a major surgical procedure … I will not be returning to work until the week after next.”

The years roll on, the excuses pile up

For years, investors have been given numerous reasons why the shares haven’t been listed, including delays in auditing, changes in jurisdictions and COVID.

There have been multiple company name changes, restructurings and share transfers between entities, all of which made it difficult for investors like Hermann to understand an already complex structure.

Sutton and Turner also seemed to find new ways to rope in investors.

Andrew Turner at his home in England.Credit:Nine

There have also been various attempts to raise new money. For instance, in 2020, Turner and some financial advisers spruiked McFaddens Australia, a wealth management company for which Sutton is listed as a director, and Trinus Impact Capital as the ultimate holding company.

“Exceptional opportunity,” one 2020 promotional document to investors says. “Currently the very wealthy are taking advantage of the exceptional opportunities that are available because of COVID-19 and they are actively buying at the bottom of the market.”

It said shareholders of McFaddens Australia would “effectively become members of an exclusive club” and would get access to McFaddens Plc’s global deal flow and insights, saying “these are normally only received by the super wealthy with a minimum net worth of $30 million”.

The proposal: investors would lend McFaddens $3 million at 15 per cent, a huge premium to the going rate, which was close to zero. For every $10,000 lent, the investor received thousands of shares in McFaddens, worth $93,390. “Immediate return of ten times with potential long term of 50 times for a riskless investment.”

It was a brazen call given markets around the world were volatile but, with templates ready to go, brochures promised investors a stock with bullish growth. One graphic showed McFaddens assets under management at $1.8 billion, ballooning to $4.8 billion by 2024.

To sweeten the deal, it said the shares they received free would be listed on the Australian Securities Exchange in the first half of 2021 “to provide liquidity for shareholders”.

Turner got behind it, writing to investors on June 9, 2020, that the plan was to now list McFaddens on the Swiss Stock Exchange. “The closest publicly listed comparison to McFaddens Australia on the ASX is Moelis Australia which listed on the ASX in 2017 and has done very well since listing and now has a market value of over $500 million,” Turner writes.

But like the other unlisted companies that investors had put their money in, including Steppes, Trinus and ASAF, McFaddens hasn’t been listed either.

Ridgway believes the various investments are “100 per cent a sham”.

“Despite my best efforts to ask them repetitively for financials and directorships and management, they refuse to give it to me,” Ridgway says. “And if they refuse to give it to me, I can only accept that they don’t have it. They don’t know it. It doesn’t exist.”

The dangling, ever-moving carrot

Kim and Darren Walker’s marriage did not survive the financial stress. Credit:Paul Harris

Darren Walker’s ex-wife Kim, a psychologist, says she feels the investors have been part of a psychological experiment. “The carrot would get dangled and continued being dangled in front of us,” she says. “These people are seeing how long they can keep us hanging on with the reward at the end being a huge sum of money. But you just have to keep waiting.”

It worked for a while, until a certain point, when Ridgway got sacked and Sutton and Turner started to withdraw. Updates became less frequent and documents that were issued had a signature of the company, not a person, which added to the opacity.

The PwC report into Aus Streaming recommended ASIC consider the actions of APC Securities (now called McFaddens Securities), run by Sutton. “The areas of concern include whether APC has engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct with regard to the financial information included in the documents produced,” the report says.

It established that Turner was central to Aus Streaming and played a key role, and Sutton was a director.

ASIC says it is investigating Sutton and Ridgway. “This matter is complex and multi-jurisdictional, involving companies and conduct across multiple countries,” it says in a statement. “It is important that ASIC undertakes its investigation in a thorough and comprehensive manner.”

Disgraced financial adviser Kris Ridgway.Credit:Louise Kennerley

ASIC did take action against Ridgway, banning him for life as an adviser, after he failed to disclose commission payments received from McFaddens Securities. But it came more than a year after this masthead first exposed his misconduct, and it was announced hours after a 60 Minutes promotion of this story aired, featuring Ridgway confessing.

Part of Ridgway’s confession included admitting to taking secret commissions, which is illegal, admitting he forged his wife’s signature more than 100 times, putting her on boards without her knowledge or consent and telling her to lie to the regulator if questioned.

“Some of my actions in recent times have been terribly unlawful,” he says. “I may not be able to be a company director. I may end up being charged with fraud and I may end up going to jail over this. And these are decisions that I made without thinking about consequences for the past couple of years. And this is going to come back to destroy me.”

But it is little comfort to investors who struggled for years, unable to access their money.

Says Kim Walker: “The stress we were under had a massive impact on our relationship and was one of the major things that led to us being divorced. So in terms of our overall life, it had a massive impact.”

Melbourne-based investor Ray Drew lost $150,000 and had to delay his retirement plans. “Depending on what age you are, you’re given a certain time in life to turn things around. Some have a bit more time up their sleeves than what I have,” he says.

Ray Drew had to delay his retirement because of the scheme.Credit:60 Minutes

Another Melbourne-based investor, Ruhan van Zyl, lost $250,000, which also took a toll. “The fact that this has been running so long, you just lose all belief in what regulators are meant to do,” he says.

Getting ASIC to act

It is an issue retired senator John Williams says he dealt with for years.

“If you ask me what’s the definition of frustration, I would say ASIC. I had 11 years trying to get them to act, trying to get them to become a fearless cop on the beat and all for nothing,” he says.

Williams travelled to Brisbane to meet some investors who had assembled from all over the country, to discuss their plight.

He says when ASIC is slow to act it sends the message of a free-for-all. “Have no fear in doing the wrong thing. We can siphon off commissions, break the law, siphon money, have no respect for the person whose money we’re investing for them because there’s no fear of punishment,” he says.

Williams says there needs to be some leadership from the treasurer and the assistant treasurer to say to ASIC: “You do your job or we’re going to sack you.”

Former senator John Williams is frustrated by ASIC’s slow action. Credit:Alex Ellinghausen

Ridgway was sacked, but there are other operators, still flying under the radar, who have put investors into dubious products.

Ridgway recently spoke to Turner about when Trinus might list. Turner told him it was most likely to be in Britain, later this year. But then again, he says, that will depend on the media.

“What we’ve got to consider and what I’m considering is any impact on this bad press. There’s no point in engaging people to spend massive amounts of money with lawyers when we know we’re going to get shit over this press. It’s got to die down,” Turner told Ridgway.

Most Viewed in Business

Source: Read Full Article