Both sides have much to lose if a delicate negotiation over limiting Iran’s activities in return for a lifting of sanctions falls short.

By David E. Sanger, Lara Jakes and Farnaz Fassihi

WASHINGTON — Days before a new hard-line president is set to be inaugurated in Iran, Biden administration officials have turned sharply pessimistic about their chances of quickly restoring the nuclear deal that President Donald J. Trump dismantled, fearing that the new government in Tehran is speeding ahead on nuclear research and production and preparing new demands for the United States.

The concerns are a reversal from just a month ago, when American negotiators, based in part on assurances from the departing Iranian government, believed they were on the cusp of reaching a deal before Ebrahim Raisi, 60, a deeply conservative former head of the judiciary, takes office on Thursday. In June, they were so confident that another round of talks was imminent that a leading American negotiator left his clothes in storage at a hotel in Vienna, where the talks took place through European intermediaries for the past four months.

That session never happened. International inspectors have been virtually blinded. At Iran’s major enrichment site at Natanz, centrifuges are spinning at supersonic speeds, beginning to enrich small amounts of nuclear fuel at near bomb-grade. Elsewhere, some uranium is being turned to metallic form — for medical purposes, the Iranians insist, though the technology is also useful for forming warheads.

It is unclear whether Mr. Raisi will retain the existing Iranian negotiating team or replace them with his own loyalists, who will presumably be determined to show they can drive a harder bargain, getting more sanctions relief in return for temporary limits on Iran’s nuclear activities.

“There’s a real risk here that they come back with unrealistic demands about what they can achieve in these talks,” Robert Malley, the lead American negotiator, said in an interview.

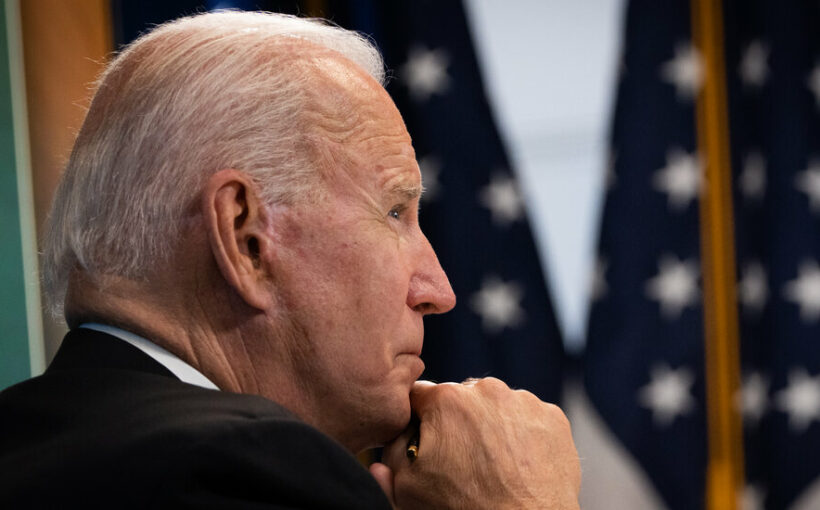

Both sides have much to lose if the diplomacy fails. For President Biden, getting the 2015 nuclear accord back on track is a top goal, in hopes of containing, once more, a nuclear program that has resumed with a vengeance three years after Mr. Trump withdrew from it. It is also critical to Mr. Biden’s effort to restore damaged relations with European allies, who negotiated the original deal, along with the United States, Russia and China.

Mr. Biden’s aides make no secret of their concerns that the Iranians are learning so much from the work now underway that in the near future, perhaps as early as this fall, it may be impossible to return to the old accord. “At that point, we will have to reassess the way forward,” Mr. Malley said. “We hope it doesn’t come to that.”

For years, Mr. Raisi was an advocate of what Iranians call the “resistance economy,” based on the argument that Iran does not need trade with the world and had no need to open up. But during the campaign, he seemed to endorse restoring the deal, perhaps because he was under pressure to show that, unlike his predecessors, he has the skill and toughness to get rid of the American-led sanctions that have ravaged his country’s economy.

Now the economic burdens, worsened by a fifth wave of the coronavirus and water shortages that are partly the result of government mismanagement, have set off violent protests.

The new president will not be the final word on whether the deal is restored. That judgment still belongs to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is believed to have lined up the support for Mr. Raisi’s election. And on Wednesday, the ayatollah echoed a key demand: that the United States provide a guarantee that it can never again walk away from the pact the way Mr. Trump did.

Source: Read Full Article