1. This is Joe Manchin’s moment

It was the morning of Friday, March 5th, and victory was in sight. Joe Biden’s first major act as president, the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, had gone to the Senate, and it appeared to be headed for a swift passage. The moderates in the Democratic caucus had quibbled over the size and duration of the bill’s weekly unemployment benefits, but those concerns were addressed, and the day began that Friday in March with the belief that all 50 Senate Democrats were ready to vote “aye.”

But when the latest text of the bill circulated that morning, one senator took a look at the text and balked. What Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia saw in print was not the deal he and his fellow Democrats had reached about the unemployment benefits and a related tax credit. And Manchin wasn’t about to get rolled. A few hours later, as the final round of voting began on the Biden relief bill, Manchin informed his colleagues that he couldn’t support the deal. He said he was thinking about voting for a Republican amendment with an even stingier version of the unemployment provision, a move that would blow up the deal Senate Democrats had brokered and possibly the entire Covid-19 relief package.

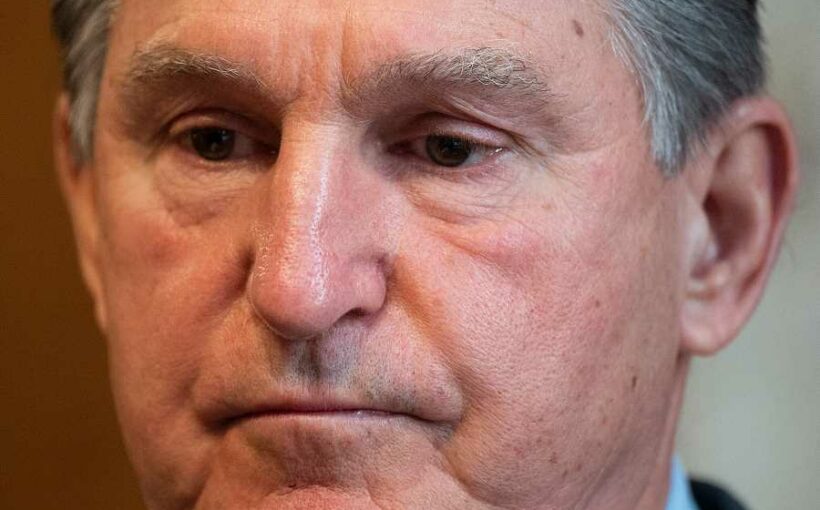

Manchin’s gambit froze the Senate. While Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and other Democrats scrambled to appease Manchin without alienating the other Democrats, the voting process was held open for nearly 12 hours, a new record in the modern history of the chamber. It took well into Saturday to reach a compromise and call the final vote. Manchin got the terms he wanted, and the American Rescue Plan passed 50 to 49, without the support of a single Republican. After the vote, Manchin was everywhere. His masked face and helmet of graying dark hair graced the front page of The New York Times. He agreed to appear on four of the five Sunday talk shows, a ubiquitous sight in a boxy blue suit and soft red tie, his Senate lapel pin twinkling in the studio lights. ABC News anchor Martha Raddatz asked, “If [Democrats are] not getting bipartisan support, which they aren’t no matter how many meetings they have, do the Democrats now have to cater to Joe Manchin’s agenda?”

The question couldn’t be more relevant. Manchin, who is 73, has served more than a decade in the Senate representing what he affectionately calls “my little state” of West Virginia. Most of that time has been in the minority. He’s watched partisanship and procedural dysfunction turn the Senate, supposedly the world’s greatest deliberative body, into a graveyard of legislation and a staging ground for presidential candidacies. In this toxic environment, Manchin crafted his own persona of the lonely centrist who just wants everyone to get along. He loves to bring up his “Republican friends” and clings to an unshakable belief that the most effective policies result from bipartisanship, give and take, negotiation.

Over the years, Manchin has milked this why-can’t-we-all-get-along act for all it’s worth. He’s able to do it because he’s always served in a divided government, when Democrats lacked the votes to do any actual legislating. In a way, he’s been able to play on everyone’s team because he wasn’t the critical vote on anything.

That changed on the night of January 5th, 2021. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock’s victories in Georgia meant Democrats would control the Senate by the slimmest of margins. Now, as the most moderate Democrat in the upper chamber, Manchin can be the decisive 50th vote on key pieces of the Biden policy agenda — or play the spoiler. He can help deliver the votes needed to reform or eliminate the filibuster — or insist, as he has so far, that negotiating with Republicans is a wiser path than changing the rules of the Senate. Either way, Manchin’s influence can’t be understated, and his colleagues know it. As one of them reportedly greeted him in the hallway of the Capitol: “Your highness.” “In a narrowly divided Senate, any one senator can be the king- or queenmaker,” says Jim Manley, a former aide to Democratic Majority Leader Harry Reid. “He’s decided he wants to be the kingmaker.”

Now that he’s arguably the most powerful senator in America, it’s worth asking: What does Manchin want? Does he have the chops to be a kingmaker? And if McConnell and the Republicans filibuster bills on voting rights, immigration, and the environment over the next two years, what will it take to change his mind?

2. Think of him like a mayor

In pre-Covid days, Manchin used to give tours of his home state to other senators and reporters. It’s an easy trip from Washington to West Virginia, about four hours by car, four and a half if you go the scenic route. The uber-wealthy Maryland and Virginia suburbs fall away fast, and the next 200 or so miles are some of the prettiest country you’ll see this side of the Mississippi. But the chasm between the nation’s capital and many parts of West Virginia is staggering — and that was the point of the tours. It’s a beautiful state wracked by poverty and addiction. It has one of the lowest median household incomes in the country. It’s the lone state in the union to see its population decline over the past 70 years. As Richard Ojeda, who ran for the House of Representatives there in 2018, put it, the choices available to a young person after high school were “dig coal, sell dope, or join the Army.”

Manchin grew up in a different West Virginia. In 1950, when he was three, its population surpassed 2 million people, the highest it’s ever been, and the coal industry was thriving, employing 125,000 souls and sustaining the economies of hundreds of small towns across the state. Farmington, where Joe lived, was one such town. The grocery store run by his grandfather, his father’s furniture shop — all of it depended on coal workers. Today, as coal continues its long decline, Farmington is a shell of itself, but generations of Manchins are still there. “They stayed,” says Nick Casey, a former state Democratic Party chairman and friend of Joe Manchin’s. “It made the Manchins not a dynasty so much as survivors.”

Manchin’s political education began at home. His father was the mayor of Farmington, and his uncle, A. James, was a political activist and legislator who helped deliver the state for John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential primary fight. (In his office, Manchin hangs a poster of JFK with a quote: “Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer.”) A. James Manchin was a rotund, bow-tied talker who never forgot a name and never left a hand unshaken. Young Joe watched his Uncle Jimmy amass a following as the head of a popular statewide program that removed cars from rivers and creeks, each vehicle disgorged celebrated with a little parade. “Let us purge our proud peaks of these jumbled jungles of junkery” was how A. James typically put it.

Manchin saw from a young age that government worked when it delivered for the people in a way you could see, feel, and touch. He also learned to heed the folks in the “little white houses,” the modest homes that dot the mountains and hollows across West Virginia. Even now, as his state’s senior U.S. senator, Manchin is known for how accessible he is, how quickly he or his office will respond to any complaint or request, how he stays connected to the people of his state. “Most people in the state have some form of a Joe Manchin story where he came through, where he showed up,” says Randy Jones, a political strategist based in Charleston. “At nonpolitical events, when the politicians show up, sometimes you get an eye roll from folks: Oh, great, the politicians are here,” Jones adds. “I don’t think that’s ever the sentiment about Manchin.”

In a state where Charleston, the largest city as well as the capital, has a population of about 45,000 people, West Virginia politics holds onto its small-town feel. Contra the nationalization of American politics, where red-team-blue-team loyalties outweigh the particulars of any one place, in West Virginia people still call their elected officials for help with potholes, barking dogs, and VA checks. Chris Kofinis, a former Senate chief of staff of Manchin’s, told me Manchin liked to tell a story about how as governor he once made his security detail stop on the highway at a construction project so that he could personally tell the crew they weren’t following the latest safety protocols.

“DON” CALLING: Manchin and Trump — pictured at the White House in 2017 — had a cordial relationship, but the senator and Joe Biden are also off to a warm start.

Evan Vucci/AP

John Perdue, a former longtime state treasurer, says Manchin stays in constant contact with his extensive network back home. “These small towns all have a mayor and a city council,” Perdue told me, “and they all matter, and he makes them feel like they’re players.” Like a small-town politician taking the temperature of his people, Manchin likes to call around the state when there’s a big vote on the calendar. According to Perdue, “He’ll say, ‘Do you think I’m on the right track? Am I doing the right thing here?’ ”

And like any good local politician, Manchin wants nothing more than to smash the stereotype of the place he calls home, to make West Virginia the kind of place where the choices for staying outnumber the reasons to leave. He won’t get a better chance to do that than as part of Biden’s dramatic vision for how government can reimagine the American economy. “I think this is the moment when West Virginia is going to get its shake,” says Nick Casey, the former state Democratic Party chairman.

3. He’s shrewder than he lets on

To grasp how Joe Manchin thinks, you have to know this: He is a negotiator, his friends and allies say, a believer of compromise. Manchin first proved himself to be a canny legislator, cutting deals as a state rep, then honed those skills even more when he was elected governor in 2004, using all the trappings of the office to win over his skeptics and get the Legislature to pass his bills. “I wore that governor’s mansion out,” he once told a reporter. “I went through more booze and food than you can imagine.” Whenever he encountered opposition to one of his plans, he demanded that all parties come together and stay there until they’d hashed out a deal. “His belief is that if we all sit in a room and come to terms with the same set of facts about who is being hurt the most, we’ll be able to come up with the best solution that addresses that fact,” says Chris Kofinis, the former chief of staff.

A year into his second term as governor, after winning re-election in a landslide, Robert Byrd, the state’s senior U.S. senator, died. On the national stage, Byrd was known as the former KKK member who rose to become a towering political figure, a man who could quote Tacitus and Montesquieu, and who had an unrivaled command of the arcane rules and procedures of the Senate. But what West Virginians usually remembered most about Byrd was his prodigious use of earmarks. Drop a pin in West Virginia and you’re liable to hit a laboratory, high school, federal agency office, or four-lane highway that Byrd made happen. “If you talk to people who are 70, 80, 90 years old and you ask what they remember about Senator Byrd, they’ll tell you about something specific in their communities,” David Satterfield, a longtime executive at West Virginia University who’s known Manchin for years, says. “They won’t talk to you about the Byrd rule or the filibuster.”

If Manchin wanted to bring West Virginia on par with its neighbors, and if he wanted to fill the void left by Byrd’s death, he would need more than a governor’s powers. The governor was constrained by balanced budgets, the whims of the Legislature, and the quirks of the state constitution; but a single senator on the right committee, as Robert Byrd had proved, could deliver in a way no governor could match.

In 2010, he got elected to the Senate, in part thanks to a TV ad that featured him firing a rifle at a sheaf of paper with “cap-and-trade” written on it, referring to the Democratic climate bill opposed by the coal industry. But like a guest who shows up just as the party’s winding down, Manchin won his race in the same year Democrats lost the House of Representatives and with it one-party control of Washington. Democrats had already lost their filibuster-proof, 60-vote majority in the Senate; they would lose the majority itself in 2014.

Still, Manchin hoped his dealmaking approach as a governor would translate to the Senate. If only he could put the right people in the room, he could get something passed. Yet time and time again, his efforts went nowhere. After the horrific mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, he tried to work with the NRA to pass background checks for gun purchases. In the end, not only did the NRA bail on him mid-negotiations and help sink the bill, but several of Manchin’s fellow Democrats voted against it. In 2018, he joined a bipartisan group of senators who introduced a compromise immigration-reform bill that would protect the 1.8 million so-called Dreamers, but that bill failed to garner 60 votes as well. Amid his failures to broker a grand bipartisan compromise, Manchin still managed to drum up some glowing PR. Time published a glowing story that described him as someone with a “bias toward action,” and that Manchin-Toomey’s defeat positioned him “as a man willing to take political risks back home for the greater good.” “Manchin in the Middle” was how Politico titled a profile of him. He was the Last of the Moderates, a decent guy who loathed the Beltway crowd and only wanted to Get Things Done.

Manchin’s critics say he misunderstands the modern Republican Party and GOP leaders like Mitch McConnell. “What he fails to realize is that, in this age, there’s no cutting deals with McConnell,” Jim Manley, the former aide to Harry Reid, told me. “Honestly, I don’t quite get it. He’s either intoxicated by all the national press he’s receiving as the key man in the Senate, or he’s doing what he thinks he needs to get re-elected in West Virginia.”

In 2014, Republicans won control of the West Virginia Legislature for the first time in 84 years; two years later, Donald Trump won the state by 42 percentage points, the second-highest margin after Wyoming. Manchin greeted the Trump presidency with outstretched arms. “I don’t think Donald Trump is far to the right,” he said on the eve of Trump’s inauguration. “I think he’s pretty much centrist — a moderate, centrist conservative Democrat.” Manchin briefly entertained rumors that he might join Trump’s cabinet and backed Trump nominees like Scott Pruitt, who ran the Environmental Protection Agency for 17 months before leaving amidst a series of scandals. Even as the sheer incompetence and mendacity of the Trump presidency piled up, Manchin lauded Trump as a president who “tries to do the reasonable thing, the responsible thing.”

“Joe Manchin doesn’t answer to the Democratic political establishment,” says one grassroots leader. “The Democratic political establishment answers to him.”

On the merits, Manchin’s assessment of Trump couldn’t have been further off the mark. But as a political strategy, it paid off. When Manchin ran for re-election in 2018, Republicans vowed they would finally oust one of the last red-state Democrats, and their Super PACs poured more than $10 million into the state to finish him off. Manchin and his Democratic allies spent even more money. In the end, he squeaked out a three-point victory. It was the closest election of his career and his most impressive, coming just two years after Trump’s resounding victory in West Virginia. Fresh off re-election, Manchin leveraged his friendship with Trump to pass a long-awaited law funding the pensions and health care benefits of retired coal miners. In the eyes of political observers inside and outside of West Virginia, he is now more or less untouchable. “Joe Manchin doesn’t answer to the Democratic political establishment,” says Stephen Smith, the founder of WV Can’t Wait, an upstart grassroots populist group. “The Democratic political establishment answers to him.”

4. If anyone gets Joe Manchin, it’s Joe Biden

Manchin’s relationship with Trump was close enough that, according to a person close to the senator, Trump would call Manchin and introduce himself as “Don.” By contrast, Manchin’s relationship with former President Obama was practically non-existent. Obama called Manchin just three times — once to congratulate him on his 2010 victory (“Don’t bring that rifle to Washington,” Obama joked, referring to the viral cap-and-trade TV ad), another time about the background-check bill, and a third time to urge him to support the Iran nuclear deal. (Manchin voted against it.) “I’ve had more personal time with Trump in two months,” he told Politico in 2017, “than I had with [Barack] Obama in eight years.”

When the Obama White House needed someone influential to put pressure on Manchin, the person close to him told me, the job fell to then-Vice President Joe Biden. It was a natural decision: Although Biden and Manchin didn’t overlap in the Senate, their backgrounds aren’t all that different — two Joes, roughly the same age, hailing from industrial states, longtime allies of labor unions, and adherents to the belief that the Senate only works when there’s bipartisan compromise.

Manchin recently told The Hill that he’s spoken with Biden half a dozen times since the president took office in January — a recognition, no doubt, of Manchin’s importance as the 50th Democratic vote. Manchin said of Biden: “I think he’s a good human being, just a good heart and a good soul, and he’s the right person at the right time for America.”

Yet four months into Biden’s presidency, Manchin represents potentially the biggest obstacle to any reform that requires a 60-vote threshold to overcome a filibuster. Despite the spike in the use of the filibuster by Republicans during Obama’s presidency, and despite all the indications that Mitch McConnell wants nothing more than to regain the Senate majority and will use the filibuster accordingly, Manchin holds fast to his belief that compromise is the best way forward. In keeping with that belief, he is one of the few Senate Democrats who defends the filibuster, calling it “a critical tool” for protecting the rights and representation of small and rural states like his. Under “no circumstance,” he wrote in an April op-ed, would he vote to weaken or abolish the filibuster.

So far, most of Manchin’s fellow Democrats appear willing to give him the leeway he wants to negotiate with Republicans without lighting him up for it. And the liberal Democrats who have criticized him, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have only strengthened his position in the eyes of his constituents back home. Harry Reid, the former Democratic majority leader of the Senate, says Manchin’s insistence on working with Republicans reflects the political changes in his state and the will of his constituents, who want to see him pushing for compromise. “He’s got a lot of patience,” Reid told me, “but I think Joe will come to the conclusion that if Republicans continue to negotiate in bad faith and remain unserious in terms of getting things done, Democrats are going to have to act without them.”

If he doesn’t reach that conclusion, and Republican obstruction escalates, Manchin can expect pressure from inside and outside his caucus, from senators in Washington and grassroots organizers in West Virginia. “The fiction of politics as being a polite conversation between left and right is hilarious to us here,” says Stephen Smith of WV Can’t Wait. “In West Virginia, we’ve always known that politics is not left versus right, it’s up versus down.”

There is, of course, some recent precedent for a bipartisanship-loving, Rust Belt Democrat changing his tune in the name of getting things accomplished. During his presidential bid, Biden offered many Manchin-esque paeans about the need for bipartisanship. “You will see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends” once Trump was gone, Biden said in 2019 on a campaign stop in New Hampshire. “If we can’t change, we’re in trouble. This nation cannot function without generating consensus.” And yet, as president, Biden has gotten wise to the GOP’s antics. When Republicans couldn’t come up with a suitable counteroffer on Covid relief, Biden pushed ahead without them and Democrats passed his $1.9 trillion package on a party-line vote. And when those Republican lawmakers cried foul, Biden said his agenda had broad support among Republican and independent voters, which was the sort of bipartisanship that truly mattered.

Both Biden and Manchin agree that the next two years — and perhaps no more — present the chance to pass transformative legislation to end the Covid-19 pandemic, repair the economy, and rebuild the nation’s infrastructure. He probably won’t get a better shot at that kind of change in his lifetime. “That’s the window,” Manchin told the Charleston Gazette-Mail in February. “That’s it. Two years. That’s all we got.”

Source: Read Full Article