By Alex Traub, The New York Times

For three summers in the late 1950s, George Stranahan lived in a remote mountain valley near Aspen, Colorado, with his only professional tools a pencil and a piece of paper. He was a graduate student in theoretical physics.

Staring at a blank page one afternoon in 1959, he made a discovery: You can’t do physics alone. You need someone to talk to. Stranahan dreamed of creating a physics think tank in the Rockies.

He was not your ordinary 27-year-old with a lofty goal. Stranahan, whose family owned Champion Spark Plug Company, had recently inherited $3 million. He assembled a group of funders, nonprofit executives and fellow physicists, and he put $38,000 toward the construction of a building.

The Aspen Center for Physics was born. It proved pivotal in the development of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, for a long time the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, and the formulation of string theory, regarded by many physicists as the most promising candidate for a “theory of everything” that would explain all the universe’s physical phenomena.

Sixty-six Nobel laureates have visited. “I’m convinced all the best physics gets done there,” Tony Leggett, one of those Nobelists, wrote on the center’s website. Another, Brian Schmidt, called the center “the place I have gone to expand my horizons for the entirety of my career.”

The center turned out to be just one part of a Rocky Mountain avalanche of businesses, nonprofits, side projects and boondoggles that made up Stranahan’s career. The only-in-America array of fields he threw himself into ranged from craft beer to free-speech activism to saloon management to childhood education, along with a dash of literary patronage.

Stranahan died May 20 in a hospital in Denver. He was 89. His wife, Patti Stranahan, said the cause was a stroke and other health problems that emerged after heart surgery.

In 1962, its first summer in operation, the Aspen Center for Physics played host to 42 physicists. Now, every year it usually turns away hundreds of applicants and welcomes more than a thousand during winter and summer sessions.

Stranahan served as the center’s first president and then as a board member. In the 1980s and ’90s, when ownership of the center’s land seemed uncertain and threats appeared from developers, including Donald Trump, Stranahan guided it through stormy local politics into gaining title to its own property, its president at that time, Michael Turner, said in a phone interview.

In 1972, Stranahan left his position at Michigan State University, where he had received tenure as a physics professor, and cut back on his involvement with the Aspen center. Two seemingly irreconcilable facts indicate the eccentricity of what followed.

In 1989, Stranahan’s family had a 35% stake in Champion Spark Plug when Cooper Industries bought the company for $800 million in cash.

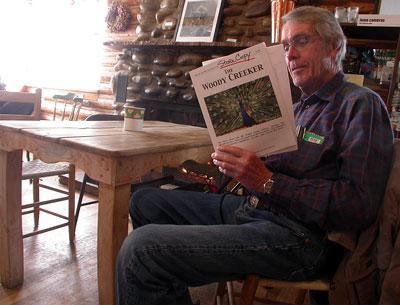

That was the scale of the fortune that Stranahan lived on. Yet in 1980, he opened a bar near Aspen, Woody Creek Tavern, where he spent several years mixing drinks while also pitching in for humbler tasks such as janitorial work. His daughter Molly remembered him as a skilled cooker of soup for customers, including ranchers and cowboys.

It did not take much to get Stranahan started on something new: He launched his single-malt manufacturer, Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey, after he watched his barn burn down alongside a volunteer fireman who, he learned, shared his appreciation of fine spirits. Soon thereafter, that fireman, Jess Graber, installed a distillery in another barn on Stranahan’s property.

This was not the kind of professional life easily summed up in the occupation box of a tax return. Stranahan called himself a “pilgrimosopher.”

He became serious about the pilgrim part in the early 1970s, when he turned much of his 1,500-acre property into a ranch for raising cattle. In 1990, Stranahan’s Limousin bull Turbo was declared grand champion at the National Western Stock Show, a highly regarded annual trade show in Denver. The price for a shot of Turbo’s semen rose to $15,000.

He quit the business not long after. Even with Turbo, Stranahan estimated that he lost $1 million during 18 years of ranching.

Stranahan earned the “-osopher” suffix when he founded the Flying Dog Brewpub in Aspen in 1990.

The company devised labels and beer names that made profane reference to feces and female dogs. In 1995, the Colorado Liquor Board pronounced Flying Dog’s labels obscene, forcing the company to remove them from the bottles of $250,000 worth of beer.

After a five-year legal battle, and with help from the American Civil Liberties Union, the brewery beat the state. In 2015, it won another legal challenge in Michigan regarding an expletive-heavy beer name.(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)“We are actually trying to spread a political message: Challenge authority,” Stranahan told the Rocky Mountain News.

Asked what “flying dog” meant, he recited a stemwinder about hiking to the summit of K2 in 1983 and having a revelation in a hotel room in Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

“The flying dog stands for doing what you should have known better, taking a risk that was maybe further out there than you expected, but pulling it off,” he said in a video produced by the company.

As of last year, Flying Dog was the 35th-biggest craft brewing company in the United States, according to the Brewers Association. In 2010, a “beer panel” convened by New York Times food critics Eric Asimov and Florence Fabricant to rank pale ales declared Flying Dog’s Doggie Style Classic its “consensus favorite.”

(END OPTIONAL TRIM.)Flying Dog’s raunchy labels are designed by illustrator Ralph Steadman, whom Stranahan met thanks to the fact that Steadman’s most famous collaborator was also a regular patron at Woody Creek Tavern: Hunter S. Thompson.

Thompson either leased or bought the land he lived on from Stranahan. The details of the arrangement, intended to be easy on Thompson, appear to have been lost in a haze of friendship and misbehavior. The first time the two men met, Stranahan told Vanity Fair in 2003, they took mescaline that hit him “like a sledgehammer.”

“We talked a lot, drank a lot and dynamited a lot,” Stranahan said about their friendship in a 2008 interview with The Denver Post. “If you’re a rancher, you have access to dynamite.”

George Secor Stranahan was born Nov. 5, 1931, in Toledo, Ohio. His father, Duane, served as vice president in charge of aviation at Champion Spark Plug, and his mother, Virginia (Secor) Stranahan, was a hospital volunteer and homemaker.

He had five siblings and an expensive education, but he grew up lonely and more interested in the reading he did on his own than in school. Physics provided a way to understand the world at a remove.

“If I could understand atoms, pretty soon I could figure out how my grandmother worked,” he explained to The New York Times in 2001.

Stranahan graduated from the California Institute of Technology in 1953, and in 1961 he received his doctorate from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University).

He began working as a professor at Michigan State in 1965, but he had a more meaningful experience teaching high schoolers in the area. He later created two charter schools, for students in grades K-8, in and around Aspen.

Stranahan’s first two marriages ended in divorce. In addition to his wife, Patti, and his daughter Molly, from his first marriage, he is survived by three other children from that marriage, Patrick, Stuart and Brie Stranahan; a son from his third marriage, Ben; a brother, Michael; a sister, Mary Stranahan; and nine grandchildren. Another son from his first marriage, Mark, died last year.

At the time of his death, Stranahan lived in Carbondale, Colorado.

When his son Ben was 7, Stranahan and Thompson “initiated” him “into manhood,” Stranahan told The Denver Post.

One night, Thompson came over to Stranahan’s place to show him a new gun. They got to drinking and talking about politics, and Ben woke up and joined them. The conversation turned to Ben’s pet tarantula, along with the notion of holding the tarantula in their hands.

“Hunter and I decided this is the moment of courage,” Stranahan recalled. Thompson reached into a bag he had brought with him, pulled out some lipstick, and gave himself and the boys a once-over.

Patti Stranahan awoke to find her husband and Thompson, both drunk, with her young son, the whole group wearing lipstick and playing with a venomous spider.

Just your typical night at home. “She turned around,” Stranahan said, “and went back to bed.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Source: Read Full Article