More On:

luxury hotels

‘Devastated’ Lady Gaga reportedly staying at luxury five-star hotel in Rome

NYC creatives live in hotels like the icons of yesteryear thanks to cheap rates

Inside spectacular staycation suites available at NYC’s top hotels this holiday season

Toddler locked inside Maserati: ‘She’s pressing the start button’

Evelyn Echols always dreamed of making her way to New York City. So, in April 1936, for her 21st birthday, she and her best friend bought cheap overnight tickets from the Midwest to the Big Apple. The first thing they did? Headed straight to Lexington Avenue and 63rd Street, maneuvered way past the men hanging around “like vultures” and booked a room at the Barbizon.

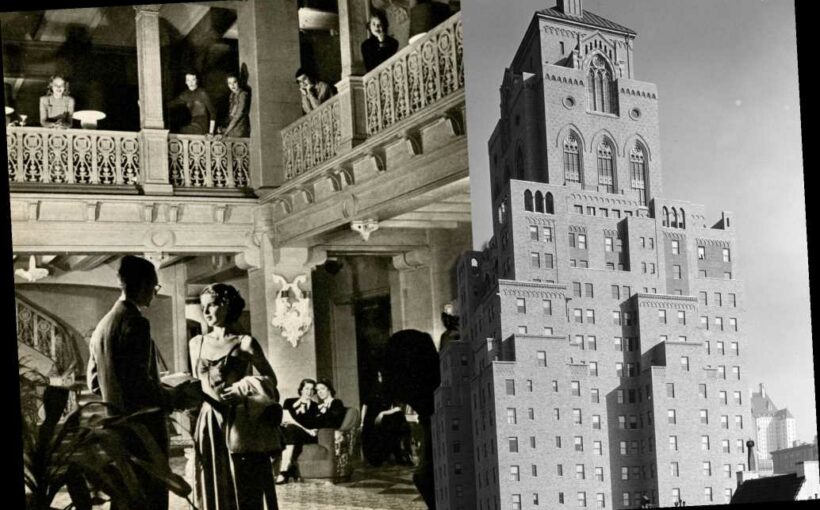

The hotel was “where almost every unmarried woman who came to New York” resided, according to historian Paulina Bren’s delightful new book “The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free” (Simon & Schuster). It’s only a slight exaggeration. Joan Crawford, Cloris Leachman, Ali MacGraw and Joan Didion all stayed there. Grace Kelly shimmied down its hallways half-naked, and a pouty Rita Hayworth posed in its gym for a Life magazine shoot, wearing a two-piece playsuit and heels.

Sylvia Plath threw all her clothes off the Barbizon’s roof on her last day as a magazine intern — an act she would later immortalize, along with the hotel, in her novel “The Bell Jar.” Judy Garland sent her daughter Liza Minnelli there, and then drove the front desk crazy when she called every three hours to check up on her.

Yet by the 1970s, the once-lively Barbizon had lost its allure. Women flung themselves off the roof. There was a murder. The lobby had a hole in the ceiling. In 2006, after several unsuccessful attempts at rebranding, the hotel was converted into luxury condominiums.

“The Barbizon is such a fascinating place,” Bren told The Post. “But it isn’t as well known as other New York institutions, like the Chelsea Hotel, and it should be.”

Her book traces the rise and fall of Manhattan’s most famous women-only residence and burnishes its reputation, not just as a boarding house for glamour girls, but as a New York City icon.

“By charting the Barbizon’s history, you can also tell the story of New York City’s 20th century and women’s place,” she said. “I wanted to reinsert the Barbizon into those histories.”

The Barbizon wasn’t the first women’s residential hotel in New York City — the Martha Washington opened in 1903. But the 1920s saw a spate of new ladies’ residences for the thousands of flappers flocking to the Big Apple in search of fame, fortune and fun. These modern women didn’t want to stay, as Bern put it, in a “dowdy old boarding house,” but they couldn’t rent an apartment on their own either.

These new residential hotels offered a solution, promising independence, respectability and also camaraderie. “They had no kitchens, so [women] wouldn’t be bogged down with chores,” Bren said. “They had daily maid service. They had common areas that were very glamorous where they could socialize, and they cost less than men’s residences — since women often had the lowest paying jobs and earned pennies to the dollar compared to men.”

You could have your moment in the sun and be free, but that moment has a sell-by date.

Paulina Bren on the Barbizon Hotel’s place in women’s liberation

The Barbizon, though, was one of a kind. The 27-floor, salmon-hued residence opened in 1928, and took its name from a 19th-century artists community outside Paris. “From the beginning the Barbizon was built as a fantasy hotel for aspiring female creatives,” Bern said.

In addition to its 720 single-occupancy rooms — so tiny that “one could open and close the door while lying in bed” — the hotel included galleries where its aspiring artists could show their work and practice rooms for budding musicians and dancers to rehearse. It also had roof gardens, several libraries, a swimming pool and a gym, as well as a restaurant and coffee shop attached.

Its first notable resident was “The Unsinkable” Molly Brown, the tenacious Titanic survivor who, after a scandalous divorce, moved to France, became an actress and was dubbed the “uncrowned queen of Paris.” In 1931, at 63, this self-proclaimed “daughter of adventure” moved back to New York and made herself at home at the Barbizon, where, despite her age, she matched the other residents’ ambition, moxie — and class.

“It was exclusive,” said Bren. No men were allowed past the lobby, and potential residents had to bring recommendation letters and references — and look the part. The severe, hawk-eyed front-desk manager, Mae Sibley, rated every girl who crossed her threshold, and gave those tenants who stayed out for too many nights in a row or dressed slovenly a stern talking-to.

“This was a respectable, glamorous place,” Bren said. It was the kind of boarding house where parents from the Midwest could feel safe sending their innocent daughters, and where elite women’s colleges and the posh Junior Leagues rented out spaces for their meetings. The Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School for secretaries rented out two whole floors for its students — who breezed in and out wearing their regulation kitten heels and white gloves — and several modeling agencies put their new recruits there.

“Eileen Ford would often pay out of her own pocket for her models who had just arrived in New York [to stay at the Barbizon],” Bren said. “It was worth it — she knew they couldn’t get up to anything since men were not allowed.”

Which isn’t to say men weren’t drawn to it. By the 1940s, the Barbizon was so chock-full of models and actresses that it became known as the “dollhouse.” Author J.D. Salinger used to pick up residents at the Barbizon’s adjacent coffee shop, telling them he was a hockey player for the Montreal Canadiens. Countless young men, meanwhile, disguised themselves as doctors (physicians were allowed to make house calls) in order to breach the hotel’s security. Mrs. Sibley called it “the oldest gag in the Barbizon.”

Not everyone who stayed at the hotel conquered New York City, of course. In 1957, journalist Gael Greene went undercover at the hotel and wrote a 10-part series, “Lone Women,” for The Post, about the hotel’s less illustrious residents: the starving artists, lonely wallflowers and spinsters who had checked into the hotel in the 1930s and never left.

“There is a deep contradiction [in the idea] of a hotel that sets women free,” said Bren. “On one hand, it allowed women a place to arrive in New York that was safe where they could pursue their dreams. Yet it could only free you up to a point because of all the social restrictions on women, particularly during the Great Depression — when women who worked were seen to be taking jobs away from men — and after World War II, when marriage really was the end goal. The Barbizon was where you could have your moment in the fun and be free, but that moment had a sell-by date.”

There were several suicides which swept the hotel in the 1950s and made headlines in the city’s tabloids. “On Sundays, one looked out the window to see if the coroner was there,” Bren writes. “It was always Sundays because Saturday was date night, and then came disappointment. Some women would hang themselves from the curtain rods.

“The Barbizon started to lose its luster when New York started to lose its luster,” said Bren. By the 1970s, as the city descended into crime and a recession, the Barbizon too began to look “run down and dowdy.”

“There was a massive hole in the stunning painted ceiling of the Italianate lobby,” Bern said. The Gibbs Secretarial School pulled out in 1972, emptying 200 rooms. Hotel occupancy dropped to 40 percent. In 1975, one of the Barbizon’s elderly residents was found murdered in her 11th-floor room.

The sexual revolution didn’t help.

“Women wanted to live on their own and didn’t want to make complex plans to have sex,” said Bern. “Plus you had a lot of feminists questioning whether the idea of separating the sexes was really liberating or not.”

The Barbizon went through various renovations after the 1970s, even opening up to men in the 1980s, until 2005, when it “became — of course — luxury condos, like much of New York City,” according to Bern.

Yet the Barbizon’s sorority spirit isn’t quite dead. Several of its old-timers — those “women” Greene had written about — refused to leave their rent-controlled units at the hotel, and the Barbizon had no choice but to give them their own space on the fourth floor. There are five such women left. And while they declined interviews, Bern did send them all copies of the book.

“It gives me great pleasure to think that they may be sitting in the beds of the Barbizon reading about the Barbizon,” said Bern. “I love that they are still there.”

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article