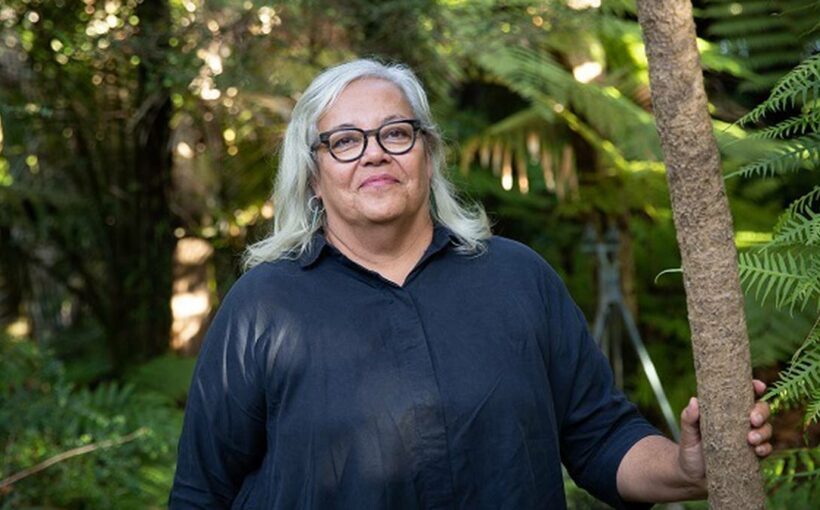

Melanie Rands, a former teacher, co-founded ecostore with husband Malcolm in 1993. She is also a visual artist, a poet and, until recently, was on the Greenpeace board. Melanie is featured as part of Auckland Museum’s Tāmaki Herenga Waka: Stories of Auckland, a new gallery that tells the stories of people and places in Tāmaki Makaurau. Free with Museum entry.

I was born in a nursing home in Mt Roskill, the youngest of six. When I was about 3, my family moved to Kawerau. Some of mum’s family were already there, and dad had an offer of a secure job at the mill and a state house right across the road from North School Primary. Our house faced the dental clinic – the “murder house” – and beyond that was Putauaki Mountain.

Dad was Fijian, Samoan and Scottish. He came to Auckland when he was discharged from the army in 1945, to finish his training as an electrician. Mum was Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongarevan and Scottish. Her mum was a dancer and her father a musician and they travelled the world with a troupe called The Hawaiian Troubadours. They were living in Singapore when mum was born, then moved to Sri Lanka, before coming to Aotearoa when mum was 9. I’m part of a long history of diaspora.

There weren’t many Pacific families in Kawerau in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and I did wonder who I was sometimes. Where was my place culturally? My parents were keen for us to fit in and for them, that meant assimilating with Pākeha culture. At 15, I was selected to go to Auckland, to a human rights conference run by Pita Sharples. It had a profound impact on my world view. I had experienced some racism at school, so it was an eye-opener to be immersed with other indigenous people talking about our experiences and what we could collectively do for a better future for Aotearoa. It was also the first time I’d learned about Te Tiriti o Waitangi and tino rangatiratanga. That was a real turning point.

I loved growing up in Kawerau. Putauaki mountain. The lake. Swimming in the river. But I also knew I had to leave. When I told my parents I wanted to go to university, mum was happy but couldn’t see a way to support me and dad made it clear we couldn’t afford it – which made me even more determined. So I applied to Teachers’ College in Hamilton, the big smoke, back when you were paid a salary to go, and got in. I was 18 and the first person in my family to do tertiary study.

My first teaching job was at Otangarei Primary in Whangarei. It was the first time I had been north of Auckland and it was where I met Malcolm. He was working at the Community Arts Council, teaching non-competitive games to school kids, and his team came to my classroom.

I was also saving to go overseas, but I didn’t go because the year I turned 24, I moved back to Whangarei and Malcolm and I got together. By then, he’d bought shares in some land with two other families from the Arts Council and they were starting an ecovillage. Malcolm took me to this bare piece of land and we sat on the hill where the house is now, and I remember looking out and wondering if I could live there. We only had two caravans and a tent. We had no electricity, so cooked on a camping stove in the caravan, or over a fire outside. We had a long-drop in the bush and our water came from the creek. I decided I was up for the adventure, which was just as well as we were expecting our first baby by then.

The broad philosophical rules of the land were, some of it would be left to regenerate back to native bush. We’d have organic gardens, never use chemical sprays, and we had ideas around active neighbouring, looking after each other’s kids who were welcome to wander between homes. Sometimes there were as many as six families, with about two acres per household and I was also teaching at Ngunguru School. I drove the “school bus”, an old Falcon, a half-hour trip each way. Although one of the kids used to eat too many lentils, so we often drove with the windows down.

In 1993 we went to Kawerau for six months, so the kids could spend time with my parents. Mum and my sister looked after our youngest while I was teaching at Putauaki school and Malcolm locked himself away in an office and drew mindmaps. When he came out, he had the genesis of what would become ecostore. We went home to the village and put our hearts and minds together. We’d had years of living in poverty, which we chose, because wanted to be available for our kids, to share parenting, and not say, ‘oh we missed that’, but it came at a cost, as money was always tight.

We started researching and found someone who was already developing safer cleaning products and we joined forces, eventually going to trade shows with our small collection of products. One early happy memory was going on a family trip to a trade show in Taranaki. We hired a bach with bunks and a kitchenette and the kids loved it, a road trip in our old bomb of a Mitsubishi was fun and also felt luxurious.

When we moved to Auckland, to expand, we lived in the back of the shop, an old boatshed in Freeman’s Bay. The kids went from being free-range on bikes and helping themselves to the neighbours’ fruit, to living in a city. We had no bathroom, so went to the Tepid Baths for showers and we cooked over a gas ring. Even though we had family there, Auckland was quite scary at first. Driving was the hardest thing, being yelled at by people, sworn at. I was such a country driver, and the noise, the sirens. I tell this story very differently to Malcolm, he is such an optimist, but we struggled. There were hard times.

I thought we’d go for a year, set up shop, it would be amazing, then return to the village. After a couple of years at the shop and doing mail-order, we realised we had to go to the next level. Everything we made was put back into the business, so it was still subsistence living and we needed to break out of that. So we found investors to make the products supermarket ready, and that led to a couple of big jumps, including manufacturing our own products.

It’s hard to say this without sounding like a total cliché – but I’m going to say it anyway – we really wanted to make a difference, by making it easier for people to find safe products to use at home. Ethics was the main thing that drove us. Yes we wanted to make a living, but we also wanted to create accessible products we believed in.

ecostore was like a third child, but by 2015 we were ready to move on. I’d worked part-time for some years by then so I could do a fine arts degree and a Masters of Creative Writing at the University of Auckland. Now, after 20 years in Auckland we’re happy to be back in Te Tai Tokerau. Our family home is finally finished, with double glazing, a new wood stove and a sleepout and the land is now home to one of the largest banana plantations in Aotearoa. There’s so much food being produced here, tamarillos, cherimoya, persimmons, figs, avocados and we’ve planted a food forest on the terraces above our house. It really stuns me when I look at early photos of our land. The hills were just covered in kikuyu and now there are trees, many of them regenerated, like nīkau from the kereru dropping seeds in their poo. The bush is incredible and last night I was woken by a kiwi.

The thing that makes us work as a couple, we’re both driven by our values, even though we have different ways of going about things. We also share an appetite for risk and we’re both creative problem solvers. That can be a source of tension at times, but it helps us. We are very conscious of the strength of our couple-ness and how much we can do together. This is a fantastic life.

www.aucklandmuseum.com

Source: Read Full Article

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/DSZBGNYXOBIRQ2NXWFMT4HI544.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/6ERU43OGQFUZVPCLUSNVSRQTNM.jpg)