On November 6, 1999 – decision day on whether Australia wanted to be a republic – a Digger stood in front of a polling booth with a placard: “No to the politicians’ republic”.

A young voter walked up and asked the Digger why, as a traditionalist, he wasn’t promoting the positive values of the constitutional monarchy. Why was he instead playing the tricky pettifogging game, led by then-prime minister John Howard, which, instead of standing up for the strengths of the monarchy, was picking holes in the exact model proposed by the Yes case, confusing and dividing voters? Why not just say the constitutional monarchy is worth defending?

Opposition leader Peter Dutton and his mentor, former Liberal prime minister John Howard.Credit:Alex Ellinghausen

An altercation ensued. It ended with the Digger snarling, “Ever fought for the crown?”

Naming Hitler in an argument usually defaults to defeat, but this time mentioning the war was the Digger’s trump card. The young voter, who hadn’t fought, respectfully backed down. (But I still thought he should have been campaigning positively for his constitutional monarchy.)

Twenty-four years on, John Howard’s party craves a win, any win, to reassure itself that it still exists. Peter Dutton, Howard’s heir, is replicating the 1999 tactic, gnawing away at the exact details of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, insinuating that a Yes vote in this year’s referendum would be putting more power in the hands of those dreaded politicians.

Earlier this month, Dutton sent the prime minister a list of 15 questions about detail. Some were already addressed in the Langton-Calma report presented to the Morrison government in July 2021; some were important in the big picture but not answerable in a referendum proposal, such as how a Voice would close the disadvantage gap; and some – such as whether a Voice would open the door to a treaty – were pure wedgy mischief-making.

Future prime minister Malcolm Turnbull was the head of the defeated Yes case in the 1999 republic referendum.Credit:Dallas Kilponen

Dutton is entitled and encouraged to ask as many questions as he likes. It is the standard 1999 play. But last time, beneath the disingenuousness, lay a widespread core belief in the constitutional monarchy. Even if Howard didn’t have the guts to centre his anti-republic campaign upon it, he knew that faith in a functional status quo rested deep in the belly of Australian conservatism. Reverence for the World War II Diggers – many of whom were still living at the time – was being fetishised in the Howard years. Like 36 of Australia’s 44 federal referendums since 1906, the republic question lost.

What corresponding core belief lies under the No case in 2023? It’s not easy, or comfortable, to locate. Simple racism would cover a percentage of voter sentiment. There is the reflex hatred of “woke” Australians who want to vote for the Voice to send a signal of solidarity to Indigenous people (which, to be frank, probably covers a large number of non-Indigenous Australians). But intolerance, either racial or political, is not a positive statement, as the belief in the constitutional monarchy was in 1999.

Requested for more detail, the prime minister did make a meal of it in radio interviews this week, but all Anthony Albanese was revealing was the impossibility of compressing that detail into soundbites. Glib, he ain’t. Scotty from marketing would have been able to do it. Anthony from accounting thinks so hard about accuracy, he sometimes forgets he’s on radio. This has cost him no votes, and his difficulty in reducing the Voice proposal into dot points may convince more voters of its seriousness.

Glib, he ain’t: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s difficulty in reducing the Voice proposal into dot points may convince more voters of its seriousness. Credit:Anna Kucera

Since 1999, when this angle of attack was used to such effect that it became a template for defeating referendums, the internet has evolved. Australians interested in the detail can find it with a few keystrokes and 15 minutes of their attention. They don’t need to be bamboozled by distrust, or have their fear or sentimentality buttons pressed as they were in 1999. They can simply go to the Langton-Calma report and choose from a short, a medium or a long version of exactly what the Voice would be.

It’s a pretty amazing document considering the current and historical complexities it had to consider. It canvassed 9400 individuals and organisations in 235 meetings across 67 communities, and accepted 4000 submissions. Furthermore, it somehow distilled this consultation into a clear design of what the Voice is (and just as importantly, what it isn’t), how it will be set up, how it will fit in with existing Indigenous structures and how its members will be chosen. In fact, every possible scenario has been thought through. Short of crossing the genre barrier by becoming a work of speculative fiction, this report anticipates every question on detail that can be asked.

The strategy of asking for more detail is not only weak and cynical, it is pre-information age. If you and I can read it, why can’t the opposition frontbench? And yet, Dutton’s tactical shadow campaign continues to rely on the worst assumptions about Australians: that they are too lazy to inquire, that they fear change, and that they cannot bring themselves to respect the Indigenous community.

I’ve reflected often on that altercation at the republic referendum polling booth in 1999. That Digger was saying that his vote carried greater weight than mine because he had literally had his skin in the game for our country. While I resented the undemocratic nature of his argument, it was impossible not to concede moral ground. While Yes voters might have disliked the disingenuous tactics, you had to accept the deep currents of feeling that supported the constitutional monarchy. There was a vibe.

There are no such currents flowing beneath this year’s No campaign. If anything, those sub-rational feelings – guilt, shame, moral debt – support the Yes case. Who has skin in the game now?

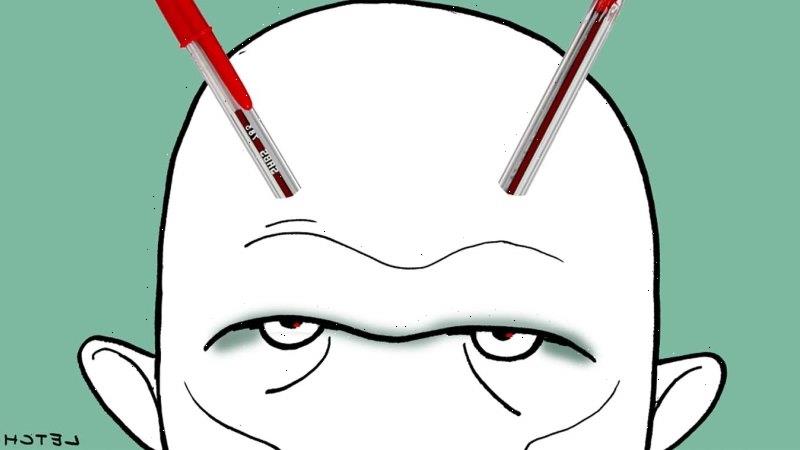

Illustration by Simon LetchCredit:

With a set of tactics to hand but no underlying principle, Dutton appears to be slowly painting himself into a corner on this referendum.

His Liberal Party has not yet stated what its final position will be. If it opts for Yes, its current unfulfillable demands for “detail” will be seen as game-playing and a waste of time. If it follows the Nationals and recommends a No vote, it will be firmly asserting itself as the party of … what? Vestigial racism (a territory the Nationals have already claimed)? Stickling for due process (really, after the last nine years)? Or accountability (sounds like a job for a permanent opposition)?

The irony for Dutton is that during the 2017 same-sex marriage debate, when his government broke its own mould and oversaw progressive change in Australia, he was credited for helping the conservatives out of a self-destructive deadlock and driving the solution of a postal plebiscite. One of that government’s few reform achievements owed itself in part to Dutton’s suggestion. He has stated a wish to redefine himself as that practical politician who can make things happen, and yet he risks – in a debate that will develop intensely through 2023 – falling into the old role of blocker and wrecker.

What does the Liberal Party stand for? Dutton has correctly and clearly identified that his party is suffering an identity crisis. But a rebellion without a cause over the Voice would reassert the very brand that he is hoping to escape: a small group of desperate individuals that became preoccupied with how to win and forgot about why.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

More from our top columnists

Home affordability: A third of the Australian population doesn’t own a home, two thirds do, so which group do politicians want to look after? Is that why they can’t answer a very simple question about Australian house prices?

The energy gap: A recent breakthrough in the creation of nuclear fusion energy is good news for climate change, but what will human civilisation do to get through the next 20 or 30 years until it becomes a reality? And will we get there?

Quick exit: Australia’s young voters are walking away from the Coalition. How does the Liberal party get them back, and why are young Australians turning away from party values – individual freedom, equality of opportunity and reward for effort – in the first place?

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article