Indiana students’ COVID vaccination fight is in the hands of Supreme Court

Exclusive interview with chronically ill student suing university: Getting the vaccine could make me backslide at this point when I am actually able to finally move forward

The Supreme Court Monday issued two unsigned opinions applying qualified immunity to disputes over alleged excessive use of force by police officers, reversing lower court decisions that allowed the officers to be sued for their on-the-job conduct.

There were no recorded dissents in the two cases, both of which involved police officers responding to domestic disputes where women or children were allegedly being threatened by adult men.

The decisions come amid a simmering debate about the doctrine of qualified immunity, which prevents government officials from being sued for violating citizens’ rights while reasonably doing their jobs unless the breached rights are “clearly established in the law.”

Democrats and libertarians, who largely oppose qualified immunity, allege that it often results in police officers who go far beyond their authority getting an unreasonable legal shield. The rare exception is if there is a case with nearly exactly the same facts that has been ruled on before.

In this April 23, 2021, file photo members of the Supreme Court pose for a group photo at the Supreme Court in Washington. Seated from left are Associate Justice Samuel Alito, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John Roberts, Associate Justice Stephen Breyer and Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Standing from left are Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Associate Justice Elena Kagan, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch and Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett. No justices dissented to two Monday decisions by the court to apply qualified immunity to cases in which police officers were being sued. (Erin Schaff/The New York Times via AP, Pool, File)

(AP)

Republicans overwhelmingly support qualified immunity, arguing that if it was taken away officers would be subject to lawsuits for nearly every difficult call they are faced with on the job. This would make it nearly impossible to recruit or retain good officers, they say.

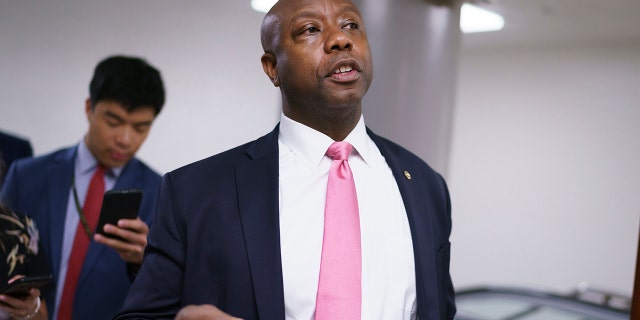

Qualified immunity was a major sticking point in the now-dead bipartisan police reform talks that dragged on and off through most of this year. Sens. Tim Scott, R-S.C., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., tried for months to come to a consensus but in the end could not.

Some Supreme Court justices – including Republican-appointed Justice Clarence Thomas – have questioned the state of the qualified immunity doctrine. Thomas said last year that he had “strong doubts” about it. Still, none of the justices dissented from the decisions to apply qualified immunity to the two cases in question Monday.

In the case of Rivas-Villegas v. Cortesluna, the Supreme Court reversed a decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals not to grant qualified immunity to Union City, California, police Officer Daniel Rivas-Villegas.

Rivas-Villegas was called to the scene of a man who was allegedly drunk and threatening his girlfriend and her two daughters – ages 12 and 15 – with a chainsaw. He and multiple other officers arrived on the scene, according to the Supreme Court’s unsigned opinion, where they ordered the man to exit the house and drop his weapon.

Officers saw that the man, Ramon Cortesluna, still had a knife in his pocket, and they ordered Cortesluna to keep his hands up and away from the knife. According to court documents, Cortesluna did not comply, at which point an unnamed officer shot him with two bean bag rounds.

Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., speaks to reporters as senators arrive for votes at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, July 13, 2021. Scott led talks on police reform for Republicans, but those discussions eventually fizzled out in part because of disagreements about qualified immunity between Republicans and Democrats. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

(AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Rivas-Villegas then approached Cortesluna, who was now on the ground, put his left knee on Cortesluna’s back, and forced his hands behind his back as another officer disarmed the man and handcuffed him.

Cortesluna sued Rivas-Villegas for excessive use of force, specifically over the fact the officer kneeled on his back, citing a previous case that established an officer violated a person’s rights by kneeling on his back. But the justices noted that the situation Rivas-Villegas responded to was “more volatile” than the previous case and therefore was “materially distinguishable” – meaning that Rivas-Villegas is protected by qualified immunity.

“In LaLonde [the precedent cited by Cortesluna], officers were responding to a mere noise complaint, whereas here they were responding to a serious alleged incident of domestic violence possibly involving a chainsaw,” the justices wrote.

In the other case decided Monday, City of Tahlequah, Oklahoma, et al. v. Austin P. Bond, the justices reversed a decision by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals not to give qualified immunity to Officers Josh Girdner and Brandon Vick in the fatal shooting of Dominic Rollice.

According to the court, Rollice’s ex-wife called the police in 2016 saying that Rollice was intoxicated and would not leave her garage. If police did not come, the woman said, “it’s going to get ugly real quick.”

After Vick, Gordner and other officers arrived and began engaging Rollice in conversation, he grabbed a hammer and positioned himself as if he were about to throw the hammer at the officers, or charge them with the hammer as a weapon, the court’s opinion described. Girdner and Vick then shot and killed Rollice. Bond, as the administrator of Rollice’s estate, sued and a Tenth Circuit panel said that the officers could not avoid being sued by invoking qualified immunity.

But the Supreme Court disagreed, saying “the officers plainly did not violate any clearly established law.”

“As we have explained, qualified immunity protects ‘all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law,’” the justices wrote. There was not the case here, the justices said, so the officers are protected by qualified immunity.

Source: Read Full Article