The outbreak of COVID-19 thrust the world of youth sports into disarray. Forced to put most activities on hold, sports leagues around the country have struggled to resume operating in a way that protects the safety of participants. Athletes of all ages were forced to reduce the amount of time they spend playing sports, or to put those activities on hold indefinitely. This has exacerbated feelings of boredom, stress, anxiety, and frustration among children of all ages.

Although the pandemic has disrupted the lives of young athletes, it has also created an unexpected opportunity to look at youth athletics with fresh eyes — and to make some much-needed changes that might not otherwise have been possible.

Over the past five years, we have been studying developments in the youth sports industry, and their impact on young athletes and their families. The rapid expansion of the industry has intensified the pressure that parents feel to increase the time, money, and energy they invest in their children’s athletic careers.

The youth sports industry increased by 55% from 2010 to 2017, and now constitutes a $19 billion market. One research organization that focuses on youth sports projects that this total will climb to $77.6 billion by 2026. Sports have long been deeply embedded in youth culture. However, the form and intensity of kids’ connection with sports has shifted in some troubling ways over the past 20 years.

A child athlete’s race to the top

The youth sports industry has evolved into a complex system with multiple layers and shifting expectations. This expansion and the commercialization of youth sports has made parenting even more confounding. In addition to negotiating their personal relationships, parents are challenged to navigate what has become a profit-driven business enterprise that treats their children as high-value customers.

Our research indicates that participating in community-based sports is no longer considered adequate in the eyes of many athletes. Rather than play on the town baseball or in the local recreational soccer league, young athletes are opting to attach themselves to clubs that play year-round. These organizations, which are generally lumped together under the umbrella term “travel team,” are more rigorous than local sports programs. They are now available for almost every sport that might interest a child. Playing for an “elite” academy, showcase, or regional team has become the new marker of status for competitive athletes and their parents.

Follow the science: Youth sports’ response to COVID-19 has failed. Here’s what we need to do now.

As travel teams have become more commonplace, adults with athletic ambitions for their children often feel pressure to secure competitive advantages for them. This leads them to sign their children up for private coaching sessions, for college showcase tournaments hours from their homes, and for membership with marketing companies that promise to attract the attention of college coaches.

And the longer a child plays competitive sports, the stronger the push to go all-in becomes. We encountered very few parents who chose to reduce the intensity of their children’s sports activities over time. When the stakes increased, so, too, did the size of the family’s investments. The race to the top, it sometimes seems, has no end point until, as is the case with the vast majority of young athletes, their playing days end, often with much disappointment.

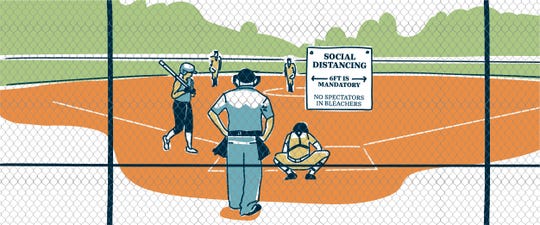

Youth sport during Covid (Photo: Jennifer Borresen)

Surely, many young athletes are benefiting from the professionalized coaching, higher levels of competition, and social bonds that travel sports often provides. But the intensification of the youth sports industry has also produced some troubling side effects. Pushing children to specialize in a single sport can have detrimental effects on their physical and psychological health. The shift from community-based leagues to travel teams has augmented pressure to begin high-intensity training at young ages. Such pressure can interfere with an athlete’s ability to sleep, eat, and derive satisfaction from playing sports.

Research also indicates that the expansion of travel sports has also led to more injuries among developing young athletes. Those who play on “elite” club teams are significantly more likely to suffer from overuse injuries than their peers who play for community-based teams. Yet this evidence tends to have minimal impact on parents eager to advance their children’s athletic careers.

Parents, take a pause

In talking with parents, we found that they tend to make decisions about their children’s athletic careers without carefully thinking through the consequences.

They sign their children up for travel teams because that is what their children’s friends seem to be doing, regardless of the long-term goals they have for their sons and daughters. And parents longer-term thinking about their child’s future subsequently develops in dialogue with other travel team parents. In this context, parents who never saw themselves as “sports parents” often find themselves into deeply engaged advocates, fans, and promoters of their children’s budding sports careers.

Walton Foundation chief: 5 ways we can help children cope with COVID-19 pandemic

The current pause in sports activity impelled by COVID-19 offers the opportunity to think carefully about how the youth sports industry can be reconfigured to better meet the needs of developing athletes. As communities prepare to return to playing, now is the time to have the hard conversations about how we want youth sports programs to serve our children and our communities.

A fan follows social distancing rules to watch a youth baseball game at the A.C. Caplinger Sports Complex in Hafer Park in Edmond, Okla. on May 18, 2020. (Photo: Doug Hoke, The Oklahoman)

Organizing games and tournaments locally could provide children with the chance to resume athletic activities and reduce their exposure to getting the coronavirus. Centering sports in neighborhood would also eliminate the need to house families in team hotels for days, another safe alternative to past practices. Ideally, this could re-establish the foundations of community-based sports that have fallen out of favor over the past two decades.

Restructuring sports leagues in this way, from the ground up, would reduce pressure on parents to sign their children up for activities that are not in their best interests. Easing back into youth sports might produce a healthier, more developmentally appropriate sports culture. It could also strengthen connections between families and their surrounding communities. Adjusting behavior, at the individual as well as the organizational levels, could provide much needed balance in the lives of developing athletes.

Christopher Bjork is professor of Education at Vassar College. Follow him on Twitter: @chbjork1. William Hoynes is dean of the faculty and professor of Sociology at Vassar College. They are currently writing a book about the influence of competitive youth sports on families in the U.S.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article